- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Read online

The Eagles Gather

A Novel

Taylor Caldwell

To M. E. Perkins

“For wheresoever the carcass is, there will the eagles be gathered together.”

St. Matthew 24:28

LIST OF CHARACTERS

ADELAIDE BURGEON BOUCHARD—widow of Jules Bouchard

Armand, Emile, Christopher—her sons

Celeste—her daughter

ANN RICHMOND BOUCHARD—widow of Honore Bouchard

Francis, Hugo, Jean, Peter—her sons

Etienne Bouchard—brother of Honore Bouchard

Henri Bouchard, Edith Bouchard—great-grandchildren of Ernest Barbour

Thomas Van Eyck—stepfather of Henri and Edith

Andre Bouchard—father-in-law of Jean Bouchard

Estelle—wife of Francis Bouchard

Annette—daughter of Armand Bouchard

Agnes—wife of Emile Bouchard

Georges Bouchard—publisher

Marion Fitts—his wife

Professor Fitts—father of Marion

AND Ernest Barbour and his nephew, Jules Bouchard, though dead, the leading characters.

CHAPTER I

Jules Bouchard, of Bouchard & Sons, munitions manufacturers, knew he was dying. He had been dying for a long time, ever since his beloved cousin, Honore Bouchard, had died on the Lusitania, while on a secret mission to the Allies. Jules had loved and trusted Honore as he had never loved or trusted any other man in his life. Honore’s chief virtue had been integrity, and Jules had had an almost ludicrous affection for this characteristic in his cousin, which seemed to him to exist apart from any of the other moralities, and to be a certain texture of the soul. It had nothing to do with honesty, thought Jules, for honesty was the last refuge of the stupid. It needed only a kind of intelligent personal ethics as its starting point: the refusal to lie to one’s self, no matter how one lied to others. It needed imagination, whereas honesty was almost always accompanied by lack of imagination.

Jules had never been one to sit back and meditate for any length of time. He was half English. Despite his Latin appearance, his delicate fastidiousness and exquisite zest in living, his fundamental character was British, which is essentially the driving character. Though he had a tremendous appreciation of all fine delicacies, all intricate perfections and lovely colors and forms and outlines, and loved nothing better than a dainty subtlety or witty paradox, he yet had the most profound contempt for all that was passionately introspective, abstract, melancholy, or sadly metaphysical. He could understand a Faust who sold his soul for youth and riches, which were the better part, but, like the founder of the Bouchard Dynasty, Ernest Barbour, Jules’ uncle, he had nothing but a loathing for a Faust that cringed and repented at the end. This loathing did not rise from incomprehension, but rather from a complete comprehension. If a man who repented was twice weak, a man who dissected his repentance was thrice damned.

He was dying. It was regrettable and a damned nuisance, but there it was. But sometimes, as he worked into the night these feverish war days, there seemed to come a stoppage in his thoughts, like a big stone thrown into the neck of a narrow stream. And without a break in his work he would think: I won’t see the end of this. Then he would go on, working a little faster, not dejected nor disturbed, but feeling only a fuming impatience, an outraged sense of interference. But lately, after these sudden stoppages, it would surprise him absently that his flesh had a coldness for a little while, an earth-coldness, as if it had chilled in anticipation.

Once he woke up in the middle of a night with a sensation of physical choking, and he discovered that he was sitting up in bed and panting. His consciousness came back very slowly, and then he was horrified to find that a sort of horror had him, a purely physical but most ghastly thing. His mind, reasonable and still calm, was yet shaken and angrily moved by this treachery of his body, this flesh-yielding to something he believed his mind had never objectively considered. This mind was like a cool, well-bred gentleman, poised and ineffably correct, caught in some way in the press of a rude, formless crowd that buffetted him, crushed him, shoved and struggled about him in an impersonal mob-terror. The gentleman might protest faintly, feel disgusted and annoyed, but he would be bruised and bedraggled anyway, and would emerge finally from the mob with a feeling that he had narrowly escaped annihilation. When this horror occurred again, with bad results the next day, he knew that the end was almost here, and he went about his preparations to meet it.

His nephew, Honore’s eldest son, Francis, was now thirty years old, and so competent, so much older in manner and appearance, so much more mature than other men of his age, that he had been unanimously elected to the presidency of The Kinsolving Arms Company a short time ago. He had little or none of his father’s inventive power, but his business faculty was formidable, his talent for organization, his shrewdness and unscrupulousness, enormous. He was an industrial genius, ferocious, expedient, and sleepless. His marriage had been carefully planned: Miss Estelle Carew was the only child of John Carew, a rising steel and railroad magnate in Pittsburgh, and one of the larger shareholders of the stock of both Bouchard & Sons and The Kinsolving Arms Company. One quarter of his blood was French, but there was nothing Latin in his tall, angular, frigid blondness, his thin sandy eyebrows, and his bitter blue eyes, like fragments of ice. Neither was there anything English or Saxon about him: he was that new type, the American, already well defined in the South and the West. He enjoyed a large popularity, but this was not because of any fundamental kindness or integrity of character or unconscious charm, but solely because he realized that popularity never hurt any one and helped considerably, and so set himself, as he did in other matters, to win friendship. His agreeable smile, his studied air of sympathy and interest, his carefully worked-out laugh, his speciously frank geniality, his ostentatious favor-granting and candid manner, won him lifelong and loyal friends. His extraordinary talent for acting can be judged by the fact that he even deceived his wife as to his real character, and beyond that no man can have a greater success. If he had any liking for any one at all, it was for his second cousin, Christopher, son of Jules.

Jean Bouchard, second son of Honore, was doing exceptionally well as second vice-president to his uncle, Andre, president of The Sessions Steel Company, and had already married his cousin, Alexa, Andre’s only daughter. Andre’s own son, Alexander, was first vice-president. Jean was a short agile young man, weighing not more than one hundred and ten pounds, but excessively active and wiry and driving. He had the dark Bouchard complexion, a surprisingly full dimpled face, a wide, white-toothed smile and small sparkling eyes. Francis had contemptuously nicknamed him “the blabber,” but it was easily observed that though he talked rapidly, and fairly constantly and very wittily, he, in reality, said nothing at all of importance, or, as he would call it himself, “incriminating.” In reality, he was much more intellectual than Francis, and very much more subtle, and, in spite of Francis’ power and strength, much more deadly. His popularity, due to his great wit and charming smile and constant good temper, came to him without conscious planning.

Hugo, the third son, had been admitted to the bar. Precise-minded and intelligent, he was one of the number of lawyers who handled the affairs of The Kinsolving Arms Company, and had already been elected to some minor civic post. He had declared his intention of running for the United States Senate within ten years, and was carefully directing all things in his life to that end. Big, bluff, already stout at twenty-seven, hearty and buff-colored, false and jovial, ready-tongued and quick in good-natured repartee, greedy and sly and winning, and a marvelously shrewd judge of human nature, he was well on the way to becoming the successful politician. Like Francis, he had marrie

d where it would do him the most good: his wife was Christine Southwood, older daughter of “Billie” Southwood, the State Boss of the Republican Party.

Had these three brothers lived in the early Middle Ages, they would most certainly have plotted against each other, and most probably one would have gathered in the entire fortune of all of them, after disposing of the other two. And no doubt that remaining one, triumphant and red-handed, would have been the second son, the small, dimpled-faced, witty, popular Jean. The deadly Jean. When they had been single they had hated one another monstrously, though maintaining, even among themselves when alone, a fraternal good temper and apparent interest in one another; each of them had hoped with great sincerity that the others would die before marriage. Now that they were all three married, the aversion one had for the others was still there, but less murderous, for the marriages were already producing children. They were all united on two things only: increasing their fortunes and hating their young brother, Peter, whom Jules Bouchard frequently referred to as “Joseph, with his father’s coat.”

Peter had indeed been given “a coat” by Honore, in the latter’s will. Knowing that his three older sons were compounded of all forty of the Thieves, he had provided carefully for Peter, who had “majored in sociology,” and had no head for business of any kind. It was a leak-proof will, as Hugo, after ruefully examining it, admitted. Peter was left outright one third of his father’s personal estate. This was in the form of a trust, yielding a rich income, half of which was to be turned over to Peter entirely at the age of thirty-five, and the rest when he was fifty. It was most evident to the brothers that Honore had feared that they might rob Peter of the first half of his legacy, but that by the time he was fifty he would most likely have developed sufficient common sense to have separated himself from his brothers. In a letter left to Peter, Honore warned him of their character, and charted for his favorite son the exact steps they would most likely take in their attempts to defraud him. In the event of Peter’s death before marriage, the estate was left to various charities.

Peter, who had a talent for writing, was amazingly like his great-uncle, Martin Barbour, of whom he had never heard much except that he had died in the Civil War. He had the same lighted blue eyes and fair complexion and light yellow hair, the same carriage and height and general good looks; he also possessed a similar character, gentle, innocent, sympathetic, and kind. “He weltered in ideals,” to quote his brothers, but there were three things about which he had no illusions and no ideals, and those three things were Francis, Jean and Hugo. Honore had underestimated Peter’s ability to read character. Everything about his brothers’ personalities was detestable to him; he had no scruples about hatred, and so hated them all completely.

Making his preparations for his death immediately after America declared war on Germany in 1917, Jules Bouchard surveyed his cousin Honore’s sons carefully, then his brother Leon’s sons, and finally his own. Leon’s son, Georges, in New York, was not dangerous, neither was Nicholas, who would take his father’s place in the bank. But Honore’s three oldest sons were very dangerous indeed, and Jules put them in juxtaposition with his own and thoughtfully studied all of them. Finally, in relief, he decided that quiet apparently stolid, thoughtful Armand was a match for Francis, in spite of the latter’s power and cunning, that both Armand and Emile would never be taken in by the charming and talkative Jean, and that Christopher, friendly though he was towards Francis could be depended upon not to trust him. As for Hugo, neither Armand nor Emile nor Christopher was deluded about him.

Another satisfying thing was the fact that Leon’s son, Nicholas, was fond of his cousins, Armand, Emile, and Christopher, and was very loyal to them. On the other hand, he disliked Francis, Jean and Hugo and Peter.

Thinking of Honore’s sons, Jules thought that Honore was probably better dead, having such sons, who would never have brought him any satisfaction or pleasure. All their lives, they had been a secret affliction to him; without Peter, he would have been completely desperate.

Reassured on his greatest anxiety, Jules then turned to the problem of his young daughter, Celeste. Whenever he thought of the girl, he experienced the only pang he ever had on account of his inexorably approaching death. He loved her as Ernest Barbour had loved his daughter, Gertrude, but with more passion and jealousy. She was a dark, sweet child with a very pretty oval face, and had, Jules said affectionately, all the virtues the rest of the family lacked. Her brothers, Armand and Emile, seemed fond of her; Armand, who had honor, would not be tempted to rob her, but there was Emile, who might not have such scruples. Jules had hated his son Christopher jealously, because of the latter’s love for his sister, but now not so oddly Jules was comforted because of it, knowing that no one would dare to rob Celeste of a penny so long as Christopher was there to guard her. Because of this, Jules was showing Christopher much more friendliness than he had ever done before, in spite of the mortal antagonism, born of mutual understanding, which existed between them.

By the time America had declared war on Germany, Jules had made all his preparations for death. No one in the family knew of his condition, though Leon uneasily suspected a little.

A man whose days are numbered usually forgets everything but enjoying himself, and seeing everything, thought Jules. But I have already enjoyed myself, and I’ve seen everything, and besides, I’m wound up like a top, and I can’t stop myself. I’ll never see the end of what I am doing now, but I’m running downhill and there are no brakes.

He was in Washington when America declared war, and he heard Wilson’s speech to Congress. He looked down from his hidden place and saw Wilson distinctly. He thought: You and I are eternities apart, and we’ve fought for two opposite worlds, bitterly and to the end, and yet the same thing has done us in.

CHAPTER II

On November 8, 1918, Jules Bouchard died.

During the days of the sixth and seventh he knew that he had only hours to live. He knew it, though his doctors, specialists from New York, who had come all the way to Windsor, believed it might even be months.

He read his newspapers, but no other news was brought to him. Oddly, he did not particularly care. He knew more than the newspapers, knew that peace was at hand. It amused him a little, that peace which he knew would be no peace. The world would be a very exciting and profitable place during the next two decades. It was too bad that he would not see it. It would be a show too delightful to miss. It was Jules Bouchard’s only regret, for everything else had become nothing, puerile at the best.

He was much amused by the expectant faces of his relatives. But he was not amused by the face of his wife, Adelaide, who had loved him passionately, in spite of a good many things. He could not be amused by her, nor by her eyes, so gentle and suffering. He said to her once: “Adelaide, don’t grieve for me, my dear. I could die more easily if I thought you wouldn’t carry on.” Again he said: “I’ve been fond of you, Adelaide, if that’s any consolation.”

One night, right in the midst of a casual conversation in the bedroom, his brother, Leon, had burst into tears. He sat there in his chair, a bulky, stocky, almost old man, his broad shoulders heaving, openly wiping his eyes. Immediately afterwards he had quarreled with his dying brother over some trifle, to cover his shame and his despair.

Little Celeste had steadfastly been refused entrance to the room. Jules had a loathing of death, and he knew that his daughter had this same loathing. She was too young to be burdened with the sight of it, he said, though the girl cried outside the door and begged him to allow her to come in. He could hear her cries streaming after her like tattered ribbons as they literally dragged her away.

Two nights before his death he sent for his eldest son, and Armand came quietly into the bedroom with its odor of drugs and starchy nurses and dissolution. Jules was unable to lie down now, and slept upright on mounds of pillows. He lay there, this night, a brown and shriveled skeleton, almost a mummy. His skull glistened through his hair; the bones of hi

s face had become prominent and sharp, his mouth drawn in a grimace of pain. But his eyes, full and brilliant and hooded, were as alive and ruthless as ever, though Armand could see the ridges of his bones under the white silk of his nightshirt as they strained with his tortured breathing.

Armand, moved beyond anything he had ever experienced before, sat down in silence. His father’s hands lay on the sheet, brown transparent wax, with knotted veins and delicate bony ridges. They moved restlessly and impatiently, though he smiled quite tranquilly at his son. With no preamble at all, he told Armand of the contents of his will. Armand listened, brooding and immobile, his eyes fixed on his father’s face. Jules’ voice was fluttering and labored, but his words were quiet and incisive.

All at once Jules laughed feebly. The nurse, who had been banished to a position outside the door, opened it a thin crack and alertly glanced in.

“Emile and Christopher will try to do you in, Armand,” said Jules. “But they can’t. At least, I don’t see how they can. You’ll be president of Bouchard & Sons, and they’ll support you, or lose everything.” Again he laughed, feebly, malevolently. “I’d like to see their faces! I’ve named you and Leon executors. But Leon won’t live long. Hearts run in our family. And another thing: Celeste’s share will be managed by Christopher.” He regarded his son with a smile that was almost gloating.

Armand’s forehead slowly puckered and wrinkled. “Why do you tell me this, now?”

Jules shrugged; his smile became more enjoying. “I’ts a pleasure I can’t deny myself—seeing, in a small way, the effect of my will before I die.”

Armand flushed dully. “Did you think, for instance, that I would rob little Celeste?”

Jules lifted his hands airily, dropped them, looked his son fully in the face. “How should I know that? Money has made devils of men before!”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

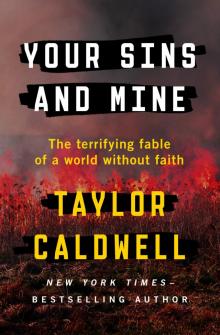

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine