- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

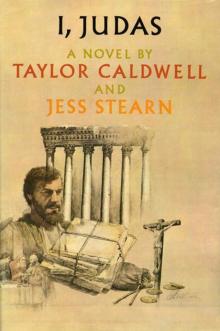

I, Judas

I, Judas Read online

I, JUDAS

Taylor Caldwell

AND

Jess Stearn

First published by

Atheneum Publishers, Inc.

1977

I, JUDAS

was betrayed by my own youth and idealism, dreaming that I could become a vital instrument to save my people and change the world.

I, JUDAS

was betrayed by the priests and high officials of the Holy Temple, who told me everything but the truth as they wove their web of intrigue.

I, JUDAS

was betrayed by Pontius Pilate, Roman Proconsul and corrupt cynic, who used a voluptuous young girl to seduce the flesh and ravish the spirit.

I, JUDAS

a novel that becomes a revelation

I, JUDAS

SPELLBINDING REVELATIONS

IN A NOVEL ABOUT THE GREATEST DRAMA OF BIBLICAL TIMES.

JUDAS, THE MYTH

History’s arch betrayer, who sold his Lord for thirty pieces of silver, and stands for all time as a figure to be rejected and reviled.

JUDAS, THE MAN

The son of wealth and power, a young rebel, an apostle who fought to suppress the lusts of his flesh and hot-blooded pride to follow Jesus, and who became the victim of a monstrously diabolical lie when he committed the act that damned him in the eyes of the world.

Now the man and not the myth comes alive in the most startling and spellbinding retelling of the greatest story ever told—the ultimate triumph of the novelist who has thrilled countless millions with her magic, Taylor Caldwell.

I, JUDAS

“Brilliant…we have to look at the story of Judas and Christ in an entirely new light.”

—BEST SELLERS

“Caldwell has the ability to take this story and make it read like a modern novel of intrigue and thrills.”

—CHATTANOOGA TIMES

“IN THE CALDWELL TRADITION…EVERY FAN WILL ENJOY IT!”

—LIBRARY JOURNAL

“The Caldwell touch immerses you in the action!”

—Pittsburgh Press

This Book Is Dedicated to

Our Late Editor and Friend,

Lee Barker,

Whose Idea it Was

FOREWORD

When the Christian Roman Emperor Justinian destroyed the great and famous library in Alexandria—which contained much of the wisdom of the world—in A.D. 500, very few of the mighty books survived, and very few of the priceless parchments written by sages. Thus humanity has been forever denied access to the gathered learning, erudition, knowledge, science, literature, poetry, and enlightenment of ages previous to Christ—and all in the name of “preserving the purity of Christianity from the corruption of pagan writings.” So said the new Christian convert, Justinian, with edifying virtue.

However, a small portion was saved from the fire, either by accident or by the action of a few quiet men who loved wisdom. Among these men was one Christian Egyptian monk, Iberias, a very learned man of an ancient Alexandrian family. He had found a partly charred manuscript, on durable Egyptian parchment, among the ruins of the awesome library, and he concealed it under his robes and took it back to his cave in the Valley of the Kings, the burial place of the Pharaohs. There, by concealed candlelight or by the light of a smoking oil lamp, he read the manuscript, which was written in highly polished Greek with some extrapolations in erudite Latin, and he understood that this book had not been written by some crude, partly literate scribe, but by a gentleman of education.

He discovered that the manuscript was really a long diary of a man’s agonized hegira through life, and that the man’s name was Judas Iscariot, and it was explained by the writer that Judas was the son of a rich and powerful Pharisee Jew family who lived in Jerusalem but who also possessed a small palace in Alexandria and another in Cairo. (His actual name was Judah-bar-Simon. He was also the son of Leah-bas-Ezekiel, daughter of Ezekiel-bar-Jacob, whose uncle was a member of the Jewish Supreme Court in Jerusalem—the Sanhedrin.)

The monk Iberias was astounded as he read the manuscript to discover that Judas Iscariot was not the impoverished thief depicted by tradition and by revolted writers, but a rich young man in his own right who’ had abandoned his devoted family and his wealth to espouse voluntary poverty—in order to follow one he truly believed was the Messiah of the ages, Joshua-bar-Joseph, a Nazarene born in Bethlehem of a virgin named Miriam-bas-Jochan, whose mother was one humble Hannah of Nazareth. (Later, Joshua was called Jesus by the Romans and Christos by the Greeks.)

Because Iberias was a prudent man, fearful of denunciation as a heretic, and a man of learning himself who feared the ignorant, he hid the manuscript carefully, for he was fascinated by the terrible story written on the parchment. He often found himself in tears when meditating on it. He knew he dared not reveal the manuscript to his brethren, who firmly believed that Judas was a thief and a betrayer who had sought thirty pieces of silver in his greed. (Acceptance of thirty pieces of silver was mandatory under the laws of the Sanhedrin, for it indicated that the betrayer had revealed his knowledge in good faith—a refusal of the silver assured the judges that the betrayer had lied.) So the puzzling fact in the Bible, that Judas threw away the thirty pieces of silver a little later—he who was supposed to have rendered up his Lord for gain—was explained in the manuscript.

There were a few intellectuals among Iberias’ brethren, men he trusted, and so he let them read the manuscript in secret. On his deathbed he conveyed the document to a beloved younger monk, and for centuries it was kept hidden in monasteries, to be read by other trusted men. It was taken all over Asia, and Europe and Africa, to be studied with reverence by a very few who were also terrified of the new arrogant and ruthless ecclesiastics arising from recently pagan societies who believed that all past wisdom and learning and writing were accursed by God (whose authors were doubtlessly in hell with all the countless multitudes born before the Christ). The truly Christian and enlightened lived in fear of these new ecclesiastics who interpreted Christianity individually and in accordance with their own bias, even if often they engaged in conflict with the Holy Father, the Pope. (The history of the Church teems with accounts of these conflicts.)

The manuscript finally came into the hands of a notable German family, lateral descendants of a bishop, and they kept the manuscript hidden for fear of confiscation and destruction. When the German family fell under the suspicious scrutiny of the Nazis, they were forced to flee to Portugal, leaving all their possessions behind, including the manuscript. These were seized by the Nazis. But a German officer who secretly loathed Hitler and feared for his country’ stole the manuscript and hid it himself, knowing that if the Nazis found it it would be destroyed as “the work of a Jew” which therefore had no verity and no value.

The manuscript has just been revealed by a member of that German family to whom it was returned. It has been carefully translated. And the reader may judge its quality for himself. But that Judas Iscariot was the son of a rich and famous Pharisee family, and himself heir to a fortune, is clearly beyond dispute.

Chapter One

JUDAS

HOW CAN ANY JEW REST while the invader still stalks his land!

My own heart is aflame.

How long, O Lord, are we to bear this tyranny? How long shall the hand of the oppressor grind us into the dust and girdle our head with thorns? I grieve for the dead but more for the living who die a thousand deaths every day. Where is our ancient pride, where the Joshuas and Davids and Maccabees who subdued adversaries as hateful as Rome?

The city is appalled, but no hand is raised against the despot, nay, not even an outcry, so craven have we become. There are only dark mutterings by the great unwashed, the humble peasants and shopkeepers, the Amharetzin, whom no decent

Pharisee or Sadducee would so much as spit at.

What matters that these dead are Galileans? They are still blood of our blood, soul of our soul, worshipping the same God. They were defenseless, unarmed, unsuspecting. Some huddled over their young, others threw themselves between the soldiers and their wives and sisters. The Romans spared nobody, young or old. There was no resistance. How does one resist in God’s own place of worship?

The bodies, grotesquely sprawled on the cobbled pavement, were strewn not only over the Court of Gentiles, but even into the Court of Israel, where some had scurried for refuge.

The massacre occurred only that morning, and many of the bodies were still warm. The Levites who toiled in the Temple were carting away the corpses and ministering to the wounded. The moans assailed my ears, and I gritted my teeth. Shaking my fist, I looked up from the littered courtyard to the Fortress Antonia and saw the red-cloaked myrmidons of Rome idly chatting. What is Jewish sorrow to these pagans? I saw a tall, commanding figure, his hairless dome of a scalp gleaming in the sun, looking down on the hell below. I could almost see the smile on the thin cruel lips. Pontius Pilate, the Procurator of Judea, was enjoying his day.

Walking rapidly, to put the melancholy scene behind me, I passed through the Court of Israel, into the Court of Women, and finally the Court of Priests. I turned past the Temple guards and moved into an antechamber, where a guard let me through at mention of my name.

My summons had come from Joseph Caiaphas, High Priest by virtue of his marriage to the daughter of a High Priest. Though I had little in common with these collaborators of Rome, I responded at once, out of curiosity if nothing more.

I paused before a gilded door. In a moment it was flung open by a Levite attendant. A man considerably shorter than myself was standing at a window, looking out on the courtyard below.

“A pretty sight, is it not?” I said.

He faced me without any warmth or seeming interest. “Come, let us talk,” he said coldly. I ignored the proffered chair and we stood staring at each other, the High Priest with a faintly ironic gleam in his dark eyes.

“I have a mission for you, Judas-bar-Simon,” he said finally.

I regarded him mistrustfully. “What does a Sadducee friend of the Romans want with me?”

He had lost some of his customary aplomb, and one had only to look out the window to understand why.

“Normally,” he said defensively, “the Romans allow us to manage our own affairs.”

“Of course,” I said. “On the holiest of holidays, the Day of Atonement, the High Priest must beg the Romans for the sacred vestments with which he performs his office. And this is independence!”

The color rushed to his cheeks. “We must learn to live with Rome. The rest of the world does. We have our own courts, administer our own religion, and collect our own taxes.”

“Yes,” I said, “and we bury our own dead.”

A ripple of impatience ruffled that haughty face.

“We have privileges. This is the only province which need not serve in the armies of the Emperor. But if we Judeans do not maintain the peace, the Romans will maintain it for us. Yes”—he shut me off with a wave of the hand—“yes, just as they do today.”

His high-bridged nose wrinkled in disdain. “I warned the Galileans, knowing the temper of Pilate, but they only smiled in that idiotic way of theirs.” His voice rose angrily as if by their imprudence they had created a problem that justified the fate that had overtaken them.

“What business was it of theirs that Pilate took the money from the Temple treasury to build his aqueduct from the Bethlehem Pool to his fortress when the pools outside the city ran dry?”

“Solomon’s Pool is sacred to all Jews for its healing waters, and so this was no provincial matter.”

Caiaphas laughed harshly. “Pilate mistook them for Judeans. Naturally, he couldn’t tell one Jew from the other.”

“The Galileans have courage.”

“This is no time for courage,” he said darkly.

“You speak to one whose namesake drove the invaders into the seas.”

“The Romans are not Syrians, and there is no Judas Maccabee on the horizon.”

I ignored his Hellenized version of Judah, for so they did with every name, even the Messiah. “There is one greater than the Maccabees who will restore Israel to its ancient glories,” I said.

He sneered. “I have known a dozen Messiases. They sprout like the winter wheat, these false prophets, and harvest only trouble for the nation.”

How could he mock what all Israel was pining for? “Isaiah told us where to look for him, and when.”

“He said that we would not know him when he came.”

“The Sadducees have no faith in the Prophets,” I said.

He had recovered some of his aplomb by now.

“We have an interest in the Messias, but we must be sure of him.”

“Without faith how can you be sure? ‘And so he came and we knew him not.’ But he will be known, as he leads Israel in triumph over all nations.”

His eyes held a glint of curiosity. “How will you know him?”

“He shall have been born in Bethlehem, of the House of David. His mother shall be a virgin, and though a King in bearing and tradition, he shall ride meekly into Jerusalem on an ass.”

Caiaphas shook his head in mock despair.

“This drivel is for the poor and the shiftless, the Amharetzin and their ilk. Who can take the son of Simon of Kerioth seriously when he speaks like a shopkeeper?”

“I am not my father’s son in all things. I am a Zealot, and care not who knows it.”

“Speak not so freely,” said Caiaphas, lowering his voice, as if fearful even to be seen with somebody of this party.

“We are zealous for Israel, zealous for the Messiah, and zealous against Rome,” I said, enjoying myself thoroughly. “Is there any crime in this?”

He motioned significantly toward the window. “What crime was there in that?”

“To demonstrate is one thing, to talk another. The Romans understand the importance of action. For this reason they rule the Greeks, who call them uncultured, and the Jews, who think them barbarians. Give the Caesars their blood money, rattle no sabers, and you may talk day and night.”

My nerves were still taut from what I had observed in the courtyard, and I was drawn irresistibly to the window once more.

“Pilate will pay dearly for this one day,” I cried.

“Remember, they are only Galileans, and, as our fathers said”—his voice contained that familiar sneer—“what good comes out of Galilee?”

“Anyone who opposes Rome is my friend.”

“Waste no tears on these clods. They are not of any tribe, but mere converts, who speak only the language of Syrian Aram, and that not well.”

“I care not about their Aramaic tongue. They suffer because they are Jews like us.”

“Like us?” The heavy eyelids, blackened with kohl, widened sardonically.

“What have Sadducees and Pharisees to do with Galileans?”

The gulf I felt was not that great. “Someday they will stand side by side with the Zealots, from Dan to Beersheba.”

Caiaphas gave me a pitying glance. “And how will this be accomplished?”

“The Messiah will lead us.”

“What makes you so sure that he even lives?”

“There was a Sibylline prophecy told to Herod the Great on his deathbed that his line would be superseded by a newborn King of Kings. Before he expired Herod ordered the execution of every male under two years in Judea. This massacre of the innocents was in the reign of Caesar Augustus thirty years ago. And that child should now be ready for his ministry.”

Caiaphas shook his head incredulously. “Even so, what assurance do you have the child survives?”

“The Prophets tell us that the child was spirited off to Egypt by his parents and raised there till it was safe to return.”

We stood looking at

each other, with thinly veiled hostility, I wondering why he had summoned me, and he, no doubt, thinking the same. The silence was broken by a rustling at the door. Two men slipped quietly into the chamber. I would have known them anywhere.

“We have come from Pilate,” said the older man, whom all of Israel would have known from his gray forked beard and tall conical hat. “For once he realizes he has acted hastily.”

This was not the Pilate I had observed in his tower, but I saw no point in arguing the matter.

“Peace unto you, O Annas,” I said, barely touching his hand.

His companion came forward and offered me an embrace.

“And how,” said the teacher Gamaliel, “does it go with the son of my dear Simon?”

“My father would be surprised,” I said stiffly, “to find his Gamaliel in this company on so dark a day for Israel.”

“Judah, Judah,” he cried, “one day your impulsive nature will do you great harm. Is it any sin for the young to listen to the gray beards?”

Though short and slight, the Rabbi Gamaliel radiated a grandeur beyond even his position as head of the Sanhedrin. He had an air of openness, but there was a glint of steel under that easy exterior. Annas showed him a certain deference in overlooking my remark.

“You are here because of the Reb Gamaliel,” he said coldly. “He feels the fruit does not fall far from the tree.”

I was not to be led off by flattery. “It is unlawful for the tribes to have anything to do with another nation. And the Sadducees dine and wine their Roman friends, and do their bidding in all things. We call ourselves Jews and our capital cities are Caesarea and Tiberias. We worship in Hellenized synagogues, and are governed by a Hellenized Sanhedrin. Small wonder that the Pharisees have greater respect from the people as interpreters of the Torah.”

Annas’ face grew grim. “You were not summoned to lecture the rulers of your state.”

“What rulers and what state?” I cried. “If not for the peasants I see in the streets, I would think I was in Rome.”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

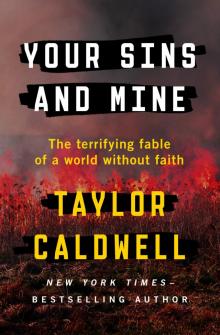

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine