- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Read online

The Earth Is the Lord’s

A Novel

Taylor Caldwell

To

Lois Dwight Cole

Any resemblance between the characters of this novel and personages living today is indignantly denied by the author! Ghost of Genghis Khan should notify author if such libelous rumor begins to circulate.

LIST OF PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

(In order of appearance)

Kurelen Uncle of Temujin

Houlun Sister of Kurelen

Kokchu Shaman (priest)

TEMUJIN (Genghis Kahn)

Son of Houlun and Yesukai

(Mighty Manslayer)

Yesukai Khan of the Yakka Mongols,

husband of Houlun

Kasar Brother of Temujin (Genghis Khan)

Bortei Wife of Temujin

Paladins of

Genghis Khan Subodai, cavalry leader

Chepe Noyon

Belgutei, half-brother of Temujin

Bektor Half-brother of Temujin

Jamuga Sechen (Jamuga the Wise)

Sworn brother of Temujin

Toghrul Khan (Prester John; Wang Khan)

Karait Turk, Nestorian Christian,

ruler of the Karait Empire

Azara Daughter of Toghrul Khan

Taliph Son of Toghrul Khan

Book One

THE LAST HARVEST

With Earth’s first Clay They did the Last Man Knead,

And there of the Last Harvest sow’d the Seed:

And the First Morning of Creation wrote

What the Last Dawn of Reckoning shall read.

—OMAR KHAYYAM

Chapter 1

Houlun sent the old serving-woman, Yasai, to the yurt of her half-brother, the crippled Kurelen. As she scuttled through the raw pink light of the sunset, the old woman wiped her hands, which were covered with blood, on her soiled garments. The dust she raised, scuttling so among the yurts, turned gold, followed her like a cloud. She found Kurelen eating as usual, smacking his lips over a silver bowl full of kumiss, fermented mare’s milk. After each filling of his mouth he would lift the silver bowl, which had been stolen from a wandering Chinese trader, and squint at it with profound admiration. He would rub a twisted and dirty finger over its delicate traceries, and a sort of voluptuous joy would shine on his dark and emaciated features.

Yasai mounted to the platform of Kurelen’s yurt. The oxen were unyoked, but they stared at her with blank brown eyes, in which the terrible sunset was reflected. The old woman paused at the opened flap of the yurt, and peered within at Kurelen. Every one despised Kurelen, because he found so many things amusing, but every one also feared him, because he hated mankind. He laughed at everything and detested everything also. Even his greed and his enormous appetite had something contemptuous about them, as though they were not a part of him, but loathsome qualities belonging to some one else, and about which he was never silent, but openly mocking.

Yasai stared at Kurelen and glowered. She was only a Karuit slave, but even she had no respect for the brother of the chieftain’s wife. She knew the story; even the herd-boys knew the story, and the shepherds, who were as stupid as the animals they drove out to pasture. Houlun had been stolen on her wedding day from her husband, a man of another tribe, by Yesukai, the Yakka Mongol. A few days later her crippled brother, Kurelen, had come to the ordu, or tent village, of Yesukai, to plead for his sister’s return. The Merkit, the clan to which Kurelen and his sister, Houlun, belonged, were shrewd folk, forest-dwelling and active traders. In sending Kurelen to Yesukai they sent a messenger who was clever and loquacious, and was possessed of a beautiful and persuasive voice. He, if any one, might be successful. If he were killed, his clan was prepared to be very philosophical about the sad event. He was a trouble-maker, and a laugher, and was disliked and hated by his people. The Merkit might not get back Houlun, but there was a fine likelihood that they might rid themselves of Kurelen. Had he been a strong and stalwart man, they might have killed him in their incomprehension and dislike. But as a cripple, and the son of a chieftain, they could not kill him. Besides, he was an exceedingly shrewd trader, and a wonderful artisan, and he could read Chinese, which was very useful in dealing with the subtle traders of Cathay. His father had said that had he been a stalwart man his people would not have killed him, for he would not have been the sort of man who deserved killing. At which sage remark the tribe had laughed heartily, but Kurelen had just made his silent wry mouth, which was singularly infuriating to simple men.

Houlun was not returned to her father’s ordu nor to her husband, for she was exceedingly beautiful and Yesukai had found her delightful in his bed. Neither did Kurelen return. It was a very uncomplicated story. He had been led to Yesukai’s tent, and the young arrogant Yakka Mongol had glowered at him ferociously. Kurelen had not been disturbed. In a mild and interested voice he asked to be shown the ordu of the young Khan. Yesukai, who had expected pleas or threats, was exceedingly nonplussed and surprised. Kurelen had not even asked for his sister, had not expressed a desire to see her, though through the corner of his eye he had observed her peeping at him behind the flap of her new husband’s yurt. Nor did he seem to be alarmed by the glowering and ominous presence of a number of young warriors, who were eyeing him fiercely.

Yesukai, who was not subtle, and thought very slowly when he thought at all, found himself leading his wife’s brother through the tent village. The women and children stood on the platforms or at the open flaps of the yurts, and stared. A profound silence filled the village. Even the horses and the home-coming cattle seemed less vociferous. Yesukai led the way, and Kurelen, limping and smiling his curious twisted smile, followed. Behind them trailed the young warriors, scowling more fiercely than ever, and wetting their lips. The dogs forgot to bark. It was a long and ludicrous journey. At intervals, Yesukai, who was beginning to feel foolish, would frown over his shoulder at the limping and following cripple. But Kurelen’s expression was artless, and had a pleased and open quality about it, like a child’s. He kept nodding his head, as though happily surprised, and muttering unintelligible comments to himself. “Twenty thousand yurts!” he said once, in a loud and musical voice. He beamed at Yesukai admiringly.

They came back to Yesukai’s yurt. At the door, Yesukai paused and waited. Now Kurelen would demand the return of his sister, or at least some large payment. But Kurelen was apparently in no hurry. He seemed thoughtful. Yesukai, who feared nothing, began to shift uneasily from foot to foot. He glowered ferociously. He fingered the Chinese dagger at his belt. His black eyes glowed with a savage fire. The warriors were tired of glowering, and began to exchange glances. Somewhere, near a distant yurt, a woman laughed openly.

Kurelen lifted one dark twisted hand to his lips and thoughtfully chewed the nails. Had he not been bent and crippled, he would have been a tall lean man. His shoulders were broad, if awry. His good leg was long, though the other was gnarled like a desert tree. His body was flat and emaciated, and the bones bent out of shape. He had a long thin face, dark and mischievous and ugly, with narrow flashing teeth, as white as milk. His cheekbones stood out like sharp shelves under slanting and glittering eyes, which were full of the light of mockery. His hair was black and long. His smile was amused and venomous.

He addressed Yesukai at last, with profound respect, in which the mockery shimmered like threads of silver. “Thou hast a lordly tribe, most valiant Khan,” he said, and his voice was soft and soothing. “Let me speak to my sister, Houlun.”

Yesukai hesitated. He had decided heretofore that Houlun was not to see her brother. But now he was impelled to grant the other’s request, though he did not know why. He waved his arm curtly at the serving-women who wer

e standing on the platform of his yurt. They brought out Houlun, and made her stand between them. She stood there, tall and beautiful and proud and hating, her gray eyes red and swollen with tears. But when she saw her brother, she smiled at him, and made a swift and involuntary movement towards him. But it was more his expression than the restraining hands of the serving-women which made her halt abruptly. He was regarding her with bland unconcern and reticence. She stood and stared at him, blinking, turning pale, while all watched. He was much loved by her, for they were the wisest and the most understanding of their father’s children, and few words were necessary between them.

He spoke to her gently, yet with a sort of mild and icy contempt. “I have seen the ordu of thy husband, Yesukai, my sister. I have walked through the village. Remain here, and be a dutiful wife to Yesukai. His people stink less than ours.”

The Mongols, who loved laughter in spite of their harsh life, at first stared at this astounding speech, and then burst into loud and roaring laughter. Yesukai laughed until the tears ran down his cheeks to his bearded lips. The warriors fell into each other’s arms. The children whooped; the women shrieked with mirth. The cattle lowed and the horses neighed and the dogs barked wildly. The herdboys and the shepherds stamped until clouds of thick dust filled the raw brightness of the desert air and made them choke.

But Houlun did not laugh. She stood there on the high platform and gazed down at her brother. Her face was as white as the mountain snows. Her white lip quivered and arched. Her eye began to flash with scorn and repudiation. And Kurelen stood below her, smiling upwards through his slanting eyes. Then at last, without a word, she turned proudly and went back into the yurt.

When the laughter subsided to a point where he could be heard, Kurelen said to Yesukai, who was openly wiping his eyes: “All men stink, but thine the least of all I have seen. Let me live in thy ordu and be one with thy people. I speak the language of Cathay; I am a bigger thief than a Bagdad Turk. I am a shrewder trader than the Naiman. I can make shields and harness, and can hammer metal into many useful shapes. I can write in the speech of Cathay and the Uighurs. I have been within the Great Wall of Cathay, and know many things. Though my body is twisted, I can be useful to thee in countless ways.”

Yesukai and his people gaped, amazed. Here was no enemy, demanding and threatening. The Shaman was angrily disappointed, and came to Yesukai’s elbow, as he hesitated, biting his lip. He whispered: “The cattle have been dying of a mysterious disease. The spirits of the Blue Sky need a sacrifice. Here is one at thy hand, O Lord. The son of a chieftain, the brother of thy wife. The spirits demand a noble sacrifice.”

The superstitious Mongol was unhappy. He needed craftsmen, and he had not been unsensible to the light of affection and joy in the eye of his beautiful and unwilling wife, Houlun, when she had seen her brother. He had been thinking that she might be more amenable if he were gracious and kindly to her brother, and that she might be happier among strangers with one of her own blood near her. But the Chief Shaman, the priest, was whispering in his ear, and he listened.

Kurelen, who hated priests, knew what was transpiring. He saw the young Khan’s hesitant eye glitter and darken as it rested on him. He saw the malignant profile of the Shaman, the cowardly and cruelly drooping lip. He saw the sly and malevolent glances, full of greed for torture and blood. He saw the suddenly dilated nostrils of the warriors, who were no longer smiling, but were drawing in closely about him. He knew he must show no fear.

He said, with amusement: “Most holy Shaman, I know not what thou art whispering, but I know that thou art whispering folly. Priests are the emasculators of men. They have the souls of jackals, and must use silly magic because they are afraid of the sword. They swell out their bellies with the meat of animals they have not hunted. They drink milk they have not taken from the mares. They lie with women they have neither bought nor stolen, nor won in combat. Because they have the hearts of camels, they would die but for their cunning. They enslave men with gibberish, in order that men may continue to serve them.”

The warriors did not like the Chief Shaman, who they suspected had an impious eye for their wives, and grinned. The Shaman surveyed Kurelen with the most malignant hatred, and his crafty face flooded with scarlet. Yesukai had begun to smile, for all his uncertainty. Kurelen turned to him.

“Answer me truly, O noble Khan: Canst thou dispense easier with one warrior than thou canst dispense with this silly priest?”

Yesukai, in his simplicity, answered at once: “A warrior is better than a Shaman. A craftsman is not as good as a warrior, but he is still better than a priest. Kurelen, if thou wilt be one of my people, I welcome thee.”

So Kurelen, who had lived all his precarious life by his wits, and his intelligence, which was very great, became a member of the tribe of Yesukai. The Shaman, who had been worsted by him, became his most terrible enemy. The warriors, who despised the defeated, no longer listened to the Shaman. But only the women and children listened.

For a long time Houlun would have nothing to do with her brother, who had betrayed and mocked her. She became pregnant by Yesukai. She tended his yurt and lay in his bed, and seemed reconciled, for she was a sagacious woman and wasted little time in grief and bewailing. Like all wise people, she made the best of circumstances, and compromised with them for the advancement of her comfort and well-being. But she would not see her brother. It was not until the hour of her labor that she sent for him. She was having a difficult time, and was afraid, and wanted the only creature she truly loved near at hand, even though he had mocked her. Her husband was away on a hunting and marauding excursion, and she had no love for him, anyway.

She knew Kurelen was detested and feared by her husband’s people. But he had been detested by his own, and she knew why. She, too, hated her kind, and despised them. But because she was cold and haughty and reserved, she was respected. Kurelen was not respected, for he was loquacious and mingled freely with the tribesmen, and was sometimes ingratiating. They thought him inferior, in consequence, and even the shepherds spoke of him contemptuously, and laughed at his cowardice. Had he not acquiesced in the rape of his sister?

The old serving-woman, Yasai, having come to the open flap of Kurelen’s yurt, stood there and stared at him. He looked up and saw her, and then lapped up the last of the kumiss, and admired, for the final time, the beautiful chasings of the silver bowl. He carefully deposited the bowl on the skin-strewn floor of the yurt, wiped his wide, thin, twisted mouth on his dirty sleeve, and smiled. “Well, Yasai?” he asked amiably.

She scowled. He was the son of a chieftain, and he spoke to her as to an equal. Her withered lips curled in uneasy contempt. They made a spitting motion, and she grunted in her old throat. Kurelen continued to eye her blandly, and waited. He folded his hands in his wide sleeves and sat there, on the floor, only his evil and mischievous eyes glinting in the hot gloom of the yurt. His amiability and lack of pride did not deceive the old woman, as they did not deceive the others, that he believed the members of the tribe of Yesukai his equals. Had he displayed pride and a consciousness of his superiority, as well as democratic amiability, they would have been flattered and grateful, and would have adored him. His very pridelessness, his very air of equality, were, they knew, merely mocking half-disguises for his awareness of their inferiority, and his mortal hatred and contempt for them.

She said curtly: “Thy sister, the wife of the Khan, wishes thee to come to her yurt.”

He raised his eyebrows, which slanted upward like black streaks. “My sister,” he said meditatively. He grinned. He got to his feet with an astonishing agility. Yasai regarded him with aversion. The simple Mongol barbarians were revolted by physical deformity. “What does she want with me?” he added, after a pause.

“She is in labor,” answered the old woman, and climbed down from the platform. She left him alone, standing in the center of his small yurt, his eyebrows dancing up and down over his eyes, his lips twisted in a half smile. His head was

bent; he seemed to be thinking curious thoughts. In spite of his deformity, and his restless eyes, and his smile, he was strangely pathetic. He went out into the raw hot light of the pink sunset.

Chapter 2

The shepherds and the herdboys were bringing in their flocks of goats and cattle. Clouds of gray and golden dust exploded about them, and the burning and glittering desert air was full of their hoarse shouts and shrill cries. The cattle complained in deep and melancholy voices, as they galloped through the winding passageways between the black, dome-shaped yurts on their wooden platforms. The tent village was pitched near the River Onon, and it was towards this yellow-gray river that the guardians of the flocks were driving their charges. Children, naked and brown, played in the gravelly dust near the yurts, but upon the thundering approach of the herds they scrambled up upon the platforms, and jeered at the shepherds as they came running by in the midst of churning hoofs and hot dust. Like phantoms the flocks went by; here and there a tossing head, a cluster of horns, a sea of tails, a plain of rumps, a forest of hairy legs, went by in this swirling and all-enveloping dust, which sparkled in the frightful glare of the sunlight.

Women, anxious about their offspring, came to the gaps of the yurts. Some had been nursing their babies, and their brown breasts hung down, full and swelling and naked. They added their shrill threats and calls to the clamor of the herd-boys and the cries of the beasts. Others emerged from the yurts with copper and wooden pails, for the animals would be milked after their return from the river. Now other shepherds were approaching, with wild and lashing stallions and mares and young colts, and the stragglers of the village prudently scurried up upon the yurt platforms. One might risk the charge of goats, but never the charge of stallions. Their savage eyes gleamed in the dust; their shaggy bodies were coated with a gray pall. Their shepherds, on horseback, cursed and shouted, and struck at the animals with long staffs. These shepherds were more savage than the stallions, and wilder. Their eyes glinted with untamed light Their dark faces ran with sweat, and their black lips were cracked with dust. The uproar was deafening, and the stench, observed Kurelen, wrinkling his nose, was insupportable.

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

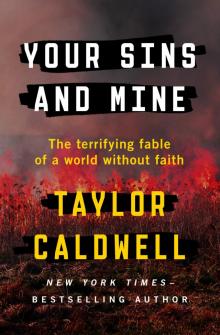

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine