- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

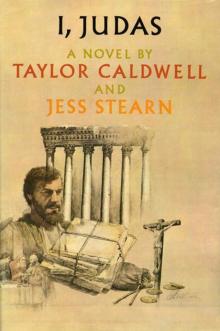

I, Judas Page 12

I, Judas Read online

Page 12

It would all work out. My mother would get over her pique, and Rachel would marry in time, given the proper dowry. She was a comely girl, but not overly bright. She would do well to marry somebody her own age.

First things came first, in any case. I had my report to deliver, and I had to stay alert, to say no more than they already knew while saying enough to keep Gamaliel’s confidence, at least. As I passed again from the Court of Gentiles into the Court of Israel, I shrugged at the sign warning Gentiles that they entered under pain of death. What a joke, for the Roman officials went wherever they liked, asking permission of nobody.

The three were waiting in the same chamber as before.

As Gamaliel embraced me, inquiring, as usual, about my mother, Caiaphas nervously tapped the floor with his foot.

“Let us hear the man,” he cried.

Gamaliel gave him a cool stare. “It will keep,” he said shortly.

I saw Annas’ warning glance. It would not do to offend Gamaliel and the Pharisee party.

Annas sat in a comfortable chair, his hands calmly folded in his lap.

“Do we have a Messias to report?” he asked with a bland expression.

“What does Sadoc tell you?” I replied boldly.

“You answer a question with a question.”

“I am not blind. Both the Baptist and the one after him”—I was reluctant to speak his name before the High Priests—“were interrogated by Sadducees and Pharisees alike. It made me wonder at my commission.”

“You tell us nothing,” growled Caiaphas.

“What can I tell you that the others haven’t?”

“Tell us of your impression, man,” Caiaphas barked. “That was your assignment.”

I had no intention of giving them any information that would bring the Master before the Sanhedrin.

“I saw nothing to convince me that either man was the Messiah, Neither claimed this role for himself.”

“Did not the Baptist salute the other as the Deliverer sent by God?”

“Even so, this would be only his opinion.”

“But it was an opinion,” said Annas, “that influenced the crowd.”

“Not the Essenes,” I countered. “They gave the Baptist precedence over the other.”

Annas looked at me closely. “Does this other not have a name?”

“He is called Joshua-bar-Joseph.”

“Was he not baptized as Jesus, and called the Anointed? Come, man, we are not fools. Why do you dally?”

I sighed heavily. “But again, this is only the Baptist speaking. Joshua-bar-Joseph claimed nothing for himself.”

“Only that he was the Son of God.”

“But he said we were all God’s children.”

Gamaliel interceded gently. “What of the crowd, Judah, how did they take it, all in all?”

“They were confused. Some had come, as I did, to determine whether the Baptist was the Messiah, only to find to their dismay that it was a mantle he would not wear.”

Gamaliel’s brow had furrowed in thought. “Joshua-bar-Joseph. The name is familiar, but it is not possible. It was so long ago. It cannot be the same.”

I had no time to think of what he said, for Annas’ eyes bored into mine. “What of your friends, the Zealots? Were they out in numbers?”

I had learned that a half-truth could be an ally in the art of dissembling. “A few were present, but they did not seem impressed by Joshua-bar-Joseph.”

“What manner of a man is he?” asked Gamaliel, with an interest he made no effort to disguise.

I hesitated, but only for a moment. “He is a simple man, a Galilean, from Nazareth, a woodworker whose father schooled him in his trade.”

Gamaliel nodded approvingly. “A very good custom, for work is the anodyne of the masses, and he who does not work becomes a trouble to himself and the state.”

Caiaphas’ foot was tapping again.

“Where is this Joshua or Jesus now? He seems to have disappeared into thin air.”

“You seem more concerned with him than the Baptist.”

“The Baptist is embarking for Perea. Herod will soon gobble him up.”

I tried not to show my surprise. “How do you know of his movements?”

“As you said,” Caiaphas rejoined carelessly, “you are not our only observer.”

“I do not seem to be of much use,” I said, not caring at this point whether I was retained or turned loose. There was little I could gain from them, except for that single slip, if such it was, revealing an agent in the ranks of the Baptist. There had been a dozen at the campfire when he disclosed his plans, but he could have discussed it with others. My mind ran over the company. The Zealots, Simon, bar-Abbas, Cestus, Dysmas, the Baptist himself, his two disciples, Jesus, the Galileans, Andrew and Simon-bar-Jonah, James and John, and me.

How could it be any of them? But then who would suspect that a grimy whiskey-monger was the stormy petrel of the revolutionary party?

Annas interrupted my reverie.

“These are parlous times for Israel. It is essential that we give Pilate no provocation.”

“He needs none,” I said, “only his natural detestation for a people different from himself.”

“We must keep an eye on this Jesus. He is more dangerous than the other.”

Gamaliel gave him a shrewd glance. “Why do you say that?”

“Fanatics we can deal with. They thrive on emotion, and that soon spends itself. But this one deals in reason, and is mild and moderate. He wears better.”

“He wishes only to bring salvation to Israel,” I said casually.

“You see,” said Annas, “already he has a champion in Judah-bar-Simon. He must be a fine talker.”

“He performed a miracle of healing.”

“We have many healers in Israel and yet the sick throng to the shrines outside the Temple and throughout the land.”

I gave vent to my frustration.

“If he were the Messiah, would he not supplant the High Priests as the principal servant of the Lord?”

Annas eyed Gamaliel speculatively before he spoke. “The High Priests have survived a dozen Messiases.”

Gamaliel’s eyes kindled.

“If he is the Messiah, he will not hurt his homeland. For then he will be a true son of Israel.”

Plainly he was different things to different people.

“You will give us another report,” said Annas.

I shrugged. “Where would you have me look?”

Annas tweaked his thin nose. “Where you know him to be,”

I would have quit the whole matter, there and then, but that it gave me a means of knowing what his adversaries were up to.

“I will do what I can,” I said, which was surely no lie.

Caiaphas had watched me malignantly. “We need somebody to watch the watcher.”

“You already have that,” I rejoined sharply.

His sallow face clouded with hostility. “I say let us move against this Jesus and be done with it.”

“With what would you charge him,” Gamaliel asked sweetly, “that he urges us to repent of our sins and believe in the one God?”

“Give him enough rope,” said Annas, “and he will hang himself.”

“And Israel with him,” muttered Caiaphas.

I was becoming increasingly aware of the underlying friction between the Nasi head of the Sanhedrin and the High Priests.

“The Sadducees,” I said along these lines, “resist even the thought of the Messiah, while the Pharisees welcome the prospect but question only his identity.”

Gamaliel gave me an approving smile. “Well said, son of a great Pharisee. Your father would be proud of you.”

Hardly, I thought wryly, his praise only serving to recall my mother’s bitter words.

The meeting had left me vaguely troubled. I allowed my mind to drift, blocking out my conscious thoughts; for the unconscious mind, I found, was a better guide at times. And then it came to me: I

had been sent to scout the Baptist, and yet there was no longer any interest in him, and no surprise that a stranger should supersede him. They were curiously well informed.

On the way out I peered into an anteroom where the sacred shew-bread was kept for the priests, and marveled at the doors and tables and candelabra of solid gold. There was a king’s ransom in this room alone, amassed by the sweat of thousands of pilgrims who faithfully paid their tithes in the hope of gaining salvation.

In the Court of Gentiles my steps took me past the whiskey stalls and I saw my beak-nosed friend still boldly hawking his wares. He spotted me at almost the same time.

“You have much business here,” he said with a leer.

“No more than yourself.”

He rubbed his dirty hands together. “Well said.” Then, looking around furtively, satisfied that nobody was in earshot, Joshua-bar-Abbas said in a hoarse undertone: “Good work, keep them guessing, but tell them nothing.”

“I have nothing to tell,” I said, “any more than you do. I assume that all our discussions are confidential.”

“You assume correctly.” He pointed dramatically to the high mound barely visible over the west wall of the Temple. “Otherwise”—he laughed without mirth—“we will all be hanging upside down on a tree of Calvary.”

“That may come,” I said pointedly, “if we do not hold our tongues.” My eyes traveled around the marketplace, from the money changers rattling their coins to the bickering and haggling over merchandise that obviously had little value except for souvenir considerations.

Bar-Abbas’ crafty face was covered with concern.

“What is it, Judah? Are you ill?”

“I was only thinking.”

He drew closer, and his evil breath turned my stomach. He played his part well.

“They must have been sour thoughts.”

“I was thinking about what you said about manufacturing a Messiah.”

“But we have one, Judah. You think so yourself.”

I studied him closely.

“Do you think so?”

He drew in some air and then let it out, laughing.

“As long as the people think so, what else does it matter?”

Chapter Six

THE MIRACLE WORKER

THE MASTER’S FAME had already preceded him. Only fifty had been invited to the wedding, but some two hundred had turned out, ostensibly to honor the bride and bridegroom, but in truth for a glimpse of the prophet who had come out of Galilee.

Simon Zelotes and I had to fight our way into the house. It was a little more elaborate than the usual clay hut with a thatched roof, for the father of the bride, Ephraim-bar-Anaim, was the wealthiest fishmonger in all of Galilee.

I saw Andrew and Simon as I came in. They were conversing with two men I had not seen before, of about my age, or perhaps a year or two younger. The two brothers hailed us as old friends. We paused for a moment, looking vainly for the Master, then walked over to greet his first disciples.

I was in for a surprise.

“These two,” said Simon, indicating the strangers, “bring the disciples to six.”

Philip and Nathaniel were ordinary-looking men, nondescriptly dressed. I saw no distinguishing features. They came from Bethsaida, like Simon and Andrew, and were also fishermen. Nathaniel had become converted through Jesus’ visualizing him under a fig tree long before he had actually seen him. This flash of clairvoyance had completely won him over. It reminded me of Simon-bar-Jonah’s fish story. On what slim premises these simple Galileans turned over their lives to God.

“And who are the other disciples?” I asked with a twinge.

“John and his brother James. They were called the day Jesus came down from the mountain.”

My eyes continued to roam over the crowd, searching for the man whose charisma had drawn me to this dreary land.

Andrew quietly put himself at our disposal. He pointed to a long table laden with rich foods of all kinds, fit rather more for the home of the High Priest or some Judean dignitary than for a Galilean fishmonger. I savored the variety of meats and game, fowl and stuffed fish, all flavored in the Jewish style with onion sauce, and a sparkling red wine which was excellent for Galilee.

“Is it proper to take refreshments before the festivities?” I inquired.

“Many guests have come a long way, and so it was thought the better part of hospitality to minister to their wants so they could join in the gladness without fretting about groaning stomachs and parched throats.”

The proud father was a kinsman of Andrew, accounting perhaps for the presence of the Master.

“And where is he?” I asked, still craning my neck.

“In the atrium, with his mother and brothers.”

“His brothers?” Somehow he had seemed a man without family.

“Joseph, Simon, Jude, and James are really his cousins, but Jesus’ father looked to their welfare when their own father died.”

“And his mother?”

“Mary is one of the wonders of our time. She looks no older than he, they would easily be taken for brother and sister.”

“There is then some resemblance?”

“Not in features, but perhaps in the radiance of their smiles. But judge for yourself.”

A young-looking woman of an almost ethereal loveliness had come through the door and appeared to be looking for someone. She was dressed in a simple white gown that fell to her feet and wore a plain gold band around her swanlike throat. Her hair had an auburn tint and was curled back on her neck as befitted a matron. Her eyes were dark and piercing, yet with a gentleness that permeated her entire countenance.

She moved gracefully, appearing almost to glide in our direction.

“Have you seen him?” she asked.

There seemed almost a conspiracy to avoid his name, as if such familiarity was a presumption, even by his own mother.

“Is there a problem?” Andrew asked.

“Because of the unexpected guests, Ephraim is embarrassed by a lack of wine.”

I wondered how this could be Jesus’ concern. He seldom imbibed himself and certainly carried no wine with him. But maybe the disciples had brought some as a gift. This was not uncommon.

Andrew showed her the greatest deference. “Let me take you to him,” he said, motioning for me to follow.

We threaded our way through the throng, everybody giving way before the solemn majesty of Andrew. I did not see Jesus at first, for a knot of people blocked him from view.

“Wherever you see a crowd,” murmured Andrew, “there is the Master at the center of it.”

He was half reclining on a couch, telling a story, when Andrew caught his eye.

He looked past Andrew at his mother, and a smile wreathed his face. She came to him and kissed him lightly on the forehead.

He rose to his feet and embraced her. “Woman,” he said fondly, “what have I to do with you at this time?”

I thought his greeting a little harsh, but it was softened by his smile. And then I remembered that in Galilee “woman” was used as a term of affection.

“They have no wine,” she said, as if that explained everything.

As I wondered why she bothered him with this irrelevant detail, he looked through the doorway at the milling crowd. “You do right to come to me, since my presence is surely the reason for the overflow of guests and the resulting shortage of wine.”

Ephraim had overheard the conversation and, as a good host, protested that Jesus should not disturb himself about such a trifle. “You, sir, are our honored guest.”

Jesus waved his objections aside.

“Summon your servants,” he said in a commanding tone.

When the servants came running, Jesus inquired how many stone waterpots were available for the ritual of purification, an important part of the wedding ceremony.

After some hesitation, they replied: ‘There are six in number, each containing some eight gallons.”

“Now fill

these pots with water and show them to me.”

Again they hesitated, looking uncertainly to their master.

Before the master could so much as nod, Jesus’ mother said quietly: “Whatever he tells you, do exactly as he says.”

Jesus trailed after them into the room where the pots were kept.

“Now fill these pots to the brim,” he ordered.

He made an airy motion of his hands and whispered under his breath, so softly that nobody could distinguish his words.

“Now,” he said, “take your pitchers and draw out the contents and take them to the governor of the wedding feast, and let him give them out to the guests.”

My eyes widened as I saw the red sparkling liquid flow into the clay pitchers. The servants seemed almost terrified by the transformation they had witnessed, while our host turned the color of alabaster. But I saw only a pleased smile on Mary’s face, and Andrew’s only concern was that Jesus may have taxed himself with this chore.

“Would you rest more?” he inquired.

“Now is the bride and bridegroom’s time, Andrew. My time has not yet come.”

We preceded Jesus into a large room where the ceremony was to be performed. I was still overcome by a confused feeling of unreality and was more curious about the wine than the couple to be wed.

I noticed the governor of the feast, a hearty man with a red face, handing out goblets of the sparkling fluid to the eager guests.

“Blessed be the creator of the fruit of these trees,” they cried, and I was again filled with wonder, for this was the toast delivered only when the wine was unadulterated by water. Had they detected water in it, the toast would have been: “Blessed be the author of the fruit of the vine.”

Ephraim, shaking his head incredulously, helped himself to several heaping beakers of the liquid, as though to drown his wonder at what had transpired before his eyes. I drew a beaker myself and sipped slowly from the wine. It was exquisite, with a bouquet such as I had never known before. And so with the others I drank to the couple, thinking at the same time how unworthy they were to be the central figures of such an occasion.

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine