- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

I, Judas Page 15

I, Judas Read online

Page 15

She was no more than fourteen when she saw this spirit and was greatly troubled. For though she had been aware, with most of Israel, of the national yearning for a Messiah, she had not for a moment associated it with herself.

She had inquired of the apparition (for what else could it be?): “How shall I be with child, when I have never known a man?”

“With God,” came the reply, “all things are possible. The Holy Spirit shall descend upon you, and you shall bear a son of God, just as Adam, before whom there was no other man, was conceived of the Holy Spirit.”

Overwhelmed by her experience, she could only murmur: “Let God’s will prevail within me. I shall be proud to be the handmaiden of the Lord.”

She was cautioned to tell none but Joseph and then only when it became necessary. He was much her senior, espousing her after the death of her parents so that he could take her into his mother’s home without causing idle tongues to wag.

I had heard whispers that the older Joseph had married her only after she was large with child. But as I looked at this saintly figure, I knew this to be false. Nevertheless, I needed to know more, to refute the attacks bound to come from the Temple.

Matthew now deferred to my questioning.

“Was Joseph then his real father?” I asked.

“He was all the father he knew from birth.”

“Then he was not born like other men?”

“He has never been like other men.”

She was amused by my clumsiness.

“We were only betrothed at the time. But in accordance with sacred custom, he respected my virtue, for he was a kindly man.”

I was so jarred at this thought that I barely heard Matthew inquire:

“Was it not difficult for a simple man to place credence in a vision he had never encountered?”

“Joseph,” replied Mary, “was no ordinary man. But”—a shadow clouded her face—“it was only natural that he should question me.” He had not chided her, but because of his mother he was sending her away to avoid scandal. Her belongings had been gathered and she was to leave in the morning for the home of her kinswoman near Jerusalem.

But that night, Joseph, too, had a vision in a dream.

“Joseph, son of David,” the angel said, “fear not to take Mary, the daughter of Abraham, as your wife. For that child which has been conceived is of the Holy Spirit.”

On rising from his slumber, Joseph announced that they would be married and raise the child together. For he, too, was honored that God had chosen him for his design.

At this time, though Mary knew it not, her kinswoman, Elizabeth, the wife of the priest Zacharias, was also with a child which appeared to have been conceived of God’s will, though not of God. For both were long beyond the age when people normally hoped for children. Indeed, Zacharias was so old that he would not even listen to the angel who brought him these tidings.

“He was standing at the Temple altar, burning incense,” Mary recalled, “when the angel Gabriel appeared and announced to him that Elizabeth would give birth to a child who would prepare the people for another sent of God.”

Zacharias calmly turned his back on the angel and proceeded with his religious duties.

How droll, but how typical for a priest to put his incense above the messenger of the Lord.

“He had seen the angel of the Lord,” I said, laughing, “but was more impressed with his ritual.”

“For his lack of faith,” she continued, “Zacharias was told he would be struck dumb until he recognized the truth. When he went to summon the people to their devotions, he found he could not speak.” But he still did not believe, for the day of visions, the Temple felt, had ceased with the Prophets of old. It was a dead God they worshipped.

Taking Elizabeth, Zacharias returned to their country home outside Jericho, not far from the Essene monastery at Qamram.

Before her own child became noticeable, Mary yielded to an impulse to see her cousin. She found the house desolate. Zacharias, still mute, was moping about with a long face, and Elizabeth, who had so long thought herself barren, was too embarrassed to leave the house.

Mary tried to lift the older woman’s spirits. “Take heart,” she said, “that you have been chosen by God to bring glad tidings to Israel.”

Elizabeth was still depressed.

“What would the Lord want of an old woman like me?”

“Have faith,” she replied, “for Zacharias’ affliction is itself evidence of God’s hand.”

She then confided her own secret.

Elizabeth was more confused than ever. “How can all this be?” she cried.

Mary had meditated long over her situation.

“God,” she had decided, “can conceive whatever he will, for neither heaven nor earth holds any secrets from him who is responsible for every form of life.”

As Mary affectionately embraced her Elizabeth felt a stirring in her own womb, and a voice told her she was filled with the Holy Spirit.

In an ecstasy of belief, she accepted now what had been so troubling before. “Blessed are you among woman,” said she, kissing Mary, “and blessed is the fruit of your womb.” Calmly she received her son’s own subordination to Mary’s unborn child.

It was difficult, observing this angelic mother, not to be impressed. And yet, why would God look for his Messiah in the humble whose lineage was their only pride?

“God,” said Mary, “has a way of putting down the mighty from their seats of power and exalting those of low degree. He fills the hungry and barren with good things and sends the rich away empty. For, in the end, all inequity is resolved.”

It seemed to me that if everything was God’s will there was little meaning in bending our efforts toward any goal.

She smiled. “We ask for strength, and God gives us difficulties, which make us strong. We pray for courage and God gives us danger, which makes us aware. We ask for favors, and God gives us challenges, which make us grow.” Her eyes glowed with an inner radiance. “And blessed is the prophet who sees all this, and gives us hope.”

Mary stayed with Elizabeth for three months, until the child was born. She had fondled it lovingly, knowing that this infant, six months senior to her own, would be his forerunner. The elderly couple had planned to call the boy Zacharias, meaning remembrance of the Lord, after the father, but Elizabeth suddenly insisted that he be called John. Zacharias’ relatives were dumfounded, since there were none by this name in their line.

“Why,” they asked suspiciously, “would you name him John?”

She looked significantly at the mute Zacharias.

“John signifies one who speaks for the Lord.”

They asked Zacharias how he would name the boy. He quickly scrawled: “Let his name be John.” And then he opened his mouth, and read the name after them, speaking for the first time in nine months.

As his family marveled, Zacharias got down on his knees and asked God for forgiveness for not recognizing that he had been favored with a vision from the Lord.

During the ceremony of circumcision, he held the baby in his arms. Although but eight days old, the infant appeared to look out on the world with wise old eyes. And he, the descendant of Aaron, who had denied the first vision now appeared to have another. For his eyes gleamed with a holy light and he peered off into the distance.

“This child,” he said in a voice filled with emotion, “shall be called the Prophet of the Highest and shall go before the face of the Lord to prepare his way. He will give light to them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death will guide their feet into the way of peace.”

And so it had all come to pass.

As she sat, childlike, her fair brow composed, it was hard to believe that all this had happened thirty years ago and more. Joseph was gone now, dead some ten years, and so were the others, but she lived on gloriously in the destiny of her son.

“He has raised up a horn of salvation for us in the house of his servant David, saying that we shoul

d be saved from our enemies, and from the hand of all who hate us. That we should remember the promise he gave our father Abraham, that he would grant unto us one who would deliver us out of the hands of our enemies so that we might serve him without fear all the days of our life.”

We regarded her silently, struck by the dignity with which she recalled God’s promise to Israel.

“And is he the one?” I asked finally.

“That is for God to say.”

“But how will we know unless he delivers us from our enemies?”

Her eyes drilled into mine.

“But who can say who that enemy is?”

“We have no enemy greater than Rome. All know there will be no peace in Israel while this enemy remains.”

“Our worst enemy is within us. There is no peace outside us, unless first found inside.”

The interview had gone on some time, and Matthew was concerned that she might be tired.

“I have so few visitors,” she said, “I am happy for this opportunity.”

His birth still intrigued me, for it was coupled with so many of the prophecies from olden times.

On that day there had been many visitors: the three astrologers, with their frankincense and myrrh; the simple shepherds who left their flocks to follow the star of Israel; Joseph of Arimathea, still loyal to mother and child, and Anna, the toothless soothsayer. Were there any others?

I saw the secret sorrow in her eyes. Her voice trembled for a moment as she flew back over the years. “There was a man Simeon, not a prophet by any means, but a simple man with a vision.”

Matthew and I exchanged glances. It seemed odd that so many had visions concerning the birth. Did coming events indeed cast their shadow before them, so that the Lord’s wishes would be known?

She did not know what vision had come to Simeon, except that he murmured gratefully that he could die happy now that he had seen the Messiah promised of God.

“Who was this Simeon?” I wondered.

She shook her head. “I knew him no more than I knew the seeress Anna or Joseph of Arimathea.” Yet she had not been surprised when the old man appeared and sank down on his knees before the newborn babe.

She closed her eyes as she recalled that day in the manger. “He took the child from me in its swaddling clothes, and he looked to the heavens, saying in a voice full of fire: ‘Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel, and for a sign which shall be spoken against.’”

Levi (whom I must now call Matthew) interposed: “And this sign, what was its nature?”

“The sign of the cross, which his disciples shall treasure until the advent of another age and his return.”

I frowned. “What is this return you speak of?”

“Our time is short indeed, if he does not deliver us from the grave.”

I could see from Matthew’s face that he was as puzzled as I was.

“Was there anything more?” he asked.

She hesitated, then said with a tiny shiver: “Simeon said that a spear would pierce my own soul at the given time.”

“Why the soul?” I asked. “Spears and swords have no effect on things of the spirit.”

She spoke with ineffable patience. “I gathered that it would be a soul-stirring event.”

“And the nature of this event?”

“We must wait and see. For God’s will may change.”

There was a hint of tears in her eyes, and Matthew said gently: “You would prefer he was like any other?”

“I have learned to share him, which is as he wants. Andrew told him one day that his family was waiting.” Her laugh was like a bell. “He spoke up: ‘Who are my mother and brothers? Whoever does the work of the Father, that is my brother and sister and my mother.’”

“You did not mind?”

“I understood the point he made. For he was born, not for one family, but for all.”

“He did not see you that day?”

“Oh, yes, he promptly came out, but he seizes on every situation to make a lesson of it, so men will better know God’s purpose.”

“And in this case it was brotherly love?”

“That all who love God are his children.”

She had put away a well-worn scroll as we came in, and now she picked it up and turned to one of its psalms. “May I read?” she asked.

Her voice was soft and melodious, like the call of the birds at daybreak.

“I will make him my firstborn, higher than the kings of the earth.

“My mercy will I keep for him for evermore, and my covenant shall stand fast with him.

“His seed also will I make to endure forever, and his throne as the days of the heaven.”

It was gratifying to see her pride. For she and Joseph had built their lives around Jesus, Mary because she believed in her vision, and Joseph because he believed in Mary. They fled to Egypt when Herod the Great’s search for the child extended from Judea into Galilee and were but a few hours ahead of Herod’s men when their boat sailed out of Joppa for Alexandria.

They had friends in Alexandria, and living in the Jewish quarter was almost like being in Jerusalem. “We had our own temples, our own worship, languages, and customs. The Jews of the Dispersal were happy to see us, and all they could talk of was the Messiah. They had heard rumors that a new prince was born in Bethlehem who would one day deliver Israel from the alien yoke, and they were anxious for the day of liberation, so they could return to Israel free men.”

It seemed odd that so many would prefer Egypt to their own land.

“But was not Egypt under Roman rule as well?” Matthew asked.

She smiled. “Yes, but the Jews of Alexandria were transients with no sense of being Egyptian, and so it mattered little to them whether they paid their taxes to Rome or the Pharaohs.”

In Alexandria, with a larger Jewish population than even Jerusalem, Jesus grew up almost as though he were in Israel. He was a prodigy, amazing not only his parents but the rabbinical community. At four he knew Hebrew, and by six, Greek and Latin. He spent his days poring over the Talmud and the Torah, and memorized the Psalms of David and the Songs of Solomon.

Daily, he went to the famous Alexandrian library, which had assembled more books on history, philosophy, and the occult than all the libraries of the world combined. He enjoyed going by himself, and Mary indulged his whim, for he seemed mature and wise even then. Sometimes she would find him in earnest discourse with the scholars and rabbis.

“They would talk about the Messiah,” said she, “and he would nod gravely at their descriptions from the Prophets.”

“None will know him when he comes,” she overheard him say once, “for a prophet has no honor in his own country, nor among his own people.”

They regarded him respectfully as he explained. “They will all want something of him that he was not sent of God to bring. The sick will demand to be healed, the poor will ask riches, and the rich would take their riches with them.” Even as a lad of eight he knew what it was to sigh. “And all desire to be liberated from Rome and be freed of taxation.”

“If the Messiah is not for the liberation of Israel,” said one scholar, “then we have been deceived all these years by Isaiah, Ezekiel, Zechariah, and Jeremiah.” His voice held just a trace of gentle irony.

The boy was not in the least disconcerted. “Salvation for Israel lies not in things of this earth but in knowing the way to eternal life.”

The Zealots scoffed at the idea of a Messiah who would not be another David or Saul.

“How else can he ascend the throne of David,” observed the insurrectionary Abbas-bar-Hedekiah, “if he does not earn that distinction against the enemy?”

The boy had smiled. “You see, even one who only speaks of the Prophets has no honor here.”

They indulged him because he was young and because of the air of remoteness which gave him a strange sort of dignity. With their little games they tested his knowledge and at the same time kept alive an

awareness of their Jewishness.

Mary had watched, bemused, as they flung their questions at him.

“Tell us,” said another scholar, “what you know of the twelve tribes of Israel?”

Jesus’ blue eyes stared out at him ingenuously.

“That which you know, sir, or that which you don’t know?”

“Name for me, sir,” the scholar mimicked, “the twelve sons of Jacob for whom the twelve tribes are named.”

“They are named,” the boy replied, “not for the twelve sons, but for the ten sons, and the two grandsons, Ephraim and Manasseh, who were the sons of Joseph, who was sold off by his brothers into slavery but became great in the land of Egypt.”

The scholar’s eyebrows arched in pleasurable surprise.

“And the ten others?”

“Reuben, Simeon, Judah”—looking at his mother, who was of the Judean tribe of David—“Zebulon, Issachar, Dan, Gad, Asher, Naphtali, and Benjamin.”

“And what of Levi, the twelfth son, what tribe did he give birth to?”

“His was the thirteenth tribe of Israel,” came the prompt reply, “but since all the land had been allotted, and the Levites had no portion of their own, certain cities supported their religious functions, and later they became Temple servants.”

All, save the dour Abbas-bar-Hedekiah, clapped their hands in pleasure.

He looked at the boy askance. “Ask this prodigy what he knows about the division of Israel, and when it will be one again,”

The boy turned the thrust with a smile.

“In the days of Rehoboam, the son of Solomon, ten tribes broke away and formed the Northern Kingdom, which was called Israel. And the Southern Kingdom, Benjamin and Judah, with Jerusalem as its capital, became known as Judah.”

Bar-Hedekiah scowled. “Any schoolboy would know that. But tell me, my young genius, when God will smile once again on a united land, free of tyranny and taxation?”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

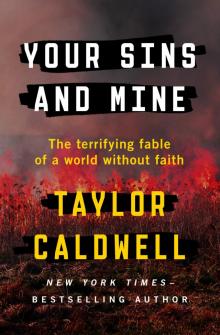

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine