- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

I, Judas Page 2

I, Judas Read online

Page 2

Annas turned with a sardonic smile to my old mentor. The Pharisee leader spoke to me gently.

“Pharisees and Sadducees,” he said, “must keep a common cause if we are to survive long enough to greet the Messiah promised by the prophet Daniel.”

“That time is already here. Even the Romans know of the coming of the King of Kings.”

“They have already found their divinity,” said Annas drily. He flipped a Roman shekel out of his purse, and held the inscription to the light. “Caesar Augustus, son of the God.”

I whipped out a coin, a Jewish silver shekel, which I held up in plain view. On one side it said clearly: “Jerusalem the Holy.” On the other were three lilies, and the legend: “I shall be as the dew unto Israel. He shall grow as the Lily.”

Annas managed a bleak smile. “Do we have three Messiases to deal with?”

“I know not the meaning of this trinity. But he shall come and the people shall adore him.”

Caiaphas had not spoken for some time. He turned querulously now, appealing to the others. “How can this hothead be trusted with so delicate a mission?”

“We can use some of that fire, properly transmuted,” said Gamaliel with a tolerant smile.

He rested his hand on my shoulder. “We share the same desire,” he said softly, “that same burning excitement over the prospect of the Messiah. The whole land is eagerly awaiting him. Some say he is already here, others that he will be shortly.”

“It cannot be too soon.”

“It has been too soon,” Annas put in wryly. “Judas the Galilean called himself the Messias and two thousand Jews died for his folly. The Romans make short work of revolutionaries.”

“True,” acknowledged Gamaliel, “there are the false prophets, but one day there will be that one.”

Annas gave him a speculative glance. “Our law stipulates that any presumed Messias must be examined by a Council of the Sanhedrin. Otherwise, he has no standing and is to be prosecuted as an impostor or worse. Better for one to die than a nation to perish.”

“The High Priest is right,” said Gamaliel. “The Romans are not ones to brook uprisings. The Galilean summoned five thousand to arms under the Maccabean banner: ‘To God alone belongs dominion.’ The bands attacked the legions, and drove the tax collectors out. For a spell, they savored the sweet smell of victory. But the long arm of Rome brought reinforcements from Parthia and Syria, and the broadsword triumphed as usual. The Galilean’s forces were hunted down like animals in the mountains and caves. The leaders were nailed to the cross. Others were carted off to the slave markets and the galleys. This lesson the Romans repeat every so often. Let us not provide them a new opportunity.”

The conversation suddenly struck me as amusing. “We sit here and chatter about things we all know and Pontius Pilate does as he pleases.”

“Pilate,” said Annas, “is no ordinary governor. In the thirty provinces of the Empire, only one procurator is permitted the company of his wife abroad.”

“And of what moment is that?”

“Some say Claudia Procula is the natural daughter of Julia, Augustus’ daughter and late wife of the Emperor Tiberius. This marriage to a Roman knight is a mark of the high favor in which Pilate is held in Rome.”

“He is no more than a glorified tax collector,” said I, “and would topple in a moment if there was a rising.”

“You speak too boldly,” chided Annas. “Nothing would suit Pilate better than a full-scale revolt. It would give him the opportunity to show Rome, by ruthlessly putting down the revolt, how valuable he might be elsewhere.”

Gamaliel broke in soothingly, “We have nothing to fear from Pilate so long as we are discreet.”

“Pilate takes pleasure in mocking us. He set the tone of his government on his arrival, flaunting in our faces the effigies of the Emperor in contradiction of our law. He gave in only when the protesters dared him to cut them to pieces.”

“Yes, he gave in,” said Gamaliel, “but he does what his ambitious master Sejanus, the new favorite, would have him do. All one has to do is look out the window.”

All I knew of Tiberius’ first minister came from the grapevine. As chief of the palace guard he had gained the confidence of a doddering Emperor by stealthily carrying out his darkest designs. He was as great an enemy of the Jews as Haman, having banished all Jews, except for Roman citizens, from Rome itself. And Pilate was his man.

“Pilate was dispatched to rid Israel of its customs,” I said. “I have that from the younger Agrippa, Herod Antipas’ brother-in-law, but it is apparent in any case. Pilate not only marched into Jerusalem flying the colors of the Twelfth Legion but put the figure of a Roman eagle over the gates of the Temple. He broods in his palace at Caesarea, and comes to the Fortress Antonia only when he means mischief to Judeans.”

“The Romans,” said Caiaphas, “care not how anybody worships so long as there is no resistance to their authority.”

“They are very much aware that too much freedom here sows dangerous ideas in the remaining provinces.”

Caiaphas gave me a sly glance. “There are other ways of conquering a people. The Romans are as much Hellenized as we.”

“Agreed, and that is the danger.”

“Yes, Judas.” He accented the second syllable of my name.

I felt the blood rush to my face. “I call myself Judah, my Hebrew name, but cannot help what others do.”

He continued to eye me sardonically. “I admire your flowered tunic of fine linen. I have seen no finer in Athens or Rome.”

“What difference what we wear? It is our hearts that count.”

“You, Judas, or should I say Judah”—he smiled mockingly—“mentioned the subversion of our customs. So they call the Messiah the Messias and the Anointed, the Christ. Is this what you object to?”

Two could play the same game. “Now I hear they are considering a ban against circumcision, through the device of forbidding mutilation.”

Caiaphas’ eyes narrowed. “They will not interfere with Jewish worship so long as the people remain orderly and pay their taxes.”

“It would surely be a scandal if the sons of the pious were not circumcised into the covenant of Abraham the customary eight days after birth.”

“This is only talk. It gives Pilate pleasure to bait the Judeans.”

“If the rite were proscribed,” I said, “it would mean a considerable loss to the Temple.”

His face quickly clouded. “The hierarchy is concerned with more basic things than money. First and foremost, we must keep Israel one.”

Whatever happened in Rome was soon common gossip in Jerusalem, borne on ready tongues of the collaborators.

“There is some strange tie between Sejanus and Pilate,” said Gamaliel thoughtfully, his eyes squinting into the late-afternoon sunlight. “After the convenient death of Germanicus, the next in line, Pilate married royally and was made a Roman knight.”

A thoughtful look crept into Annas’ cunning face. “He was rewarded with one hand, and with the other sent to an obscure province.”

“It is whispered,” said Caiaphas, “that Tiberius’ friend Calpurnius Piso had a potion put in Germanicus’ wine.”

Annas’ crafty eyes lit up. “Yes, and Pilate was the instrument.”

I found this petty intrigue tiresome. “But what has this to do with Israel?”

“We contend with a restless, ambitious functionary, frustrated by his exile.”

“And with it all,” put in Gamaliel, “He is backed to the hilt by Sejanus, who keeps him here.”

I shrugged disdainfully.

“The renegade prince Agrippa told me in Rome that Sejanus would ride high for a while, then go the way of all palace favorites. The Emperor who cheerfully disposed of his own nephew will not hesitate to cut down a lesser rival.”

Both Annas and Caiaphas seemed impressed by my remark, and even Gamaliel looked at me with new eyes.

“You are indeed your father’s son,” said An

nas, with an approving glance. “We just hope for the winds of change.”

I saw no distinctions between Romans. “Our great friends Pompey, Marcus Crassus, and Cassius invaded the Holy of Holies, desecrated the Ark of the Covenant, and stripped the sanctuary of its golden doors and altars. And you speak of Roman friendship.”

“Their depredations have not gone unanswered.” He gave that silky smile I mistrusted so much. “Think how these three died, violently, in alien lands, mocked by their enemies. The Holy One looks over the Chosen in his own way.”

I shook my head vigorously. “Judah Maccabee demonstrated that God helps those who help themselves. Not until his armies conquered the Syrian hosts did God’s light shine once more on Israel.”

“The Lord rode with the Hasmoneans on that day,” said the Reb Gamaliel, “just as he did with Joshua outside the walls of Jericho.”

“Then the Lord must have approved the Maccabeans shedding blood on the Sabbath. For until the Maccabeans’ revocation of the Sabbath laws, the Chosen preferred to be massacred in their homes and caves rather than defend themselves.”

Annas and Caiaphas raised their eyebrows. “The Sabbath belongs to God. Anything else is blasphemy.”

I made short work of such hypocrisy. “In the Temple, on Hanukkah, we celebrate the Hasmonean liberation of Israel, even though for only a hundred years. And the High Priests take sacrificial offerings, celebrating this rededication of the defiled Temple, regardless of the desecration of the Sabbath which made this holiday possible.”

There was an awkward silence, which Gamaliel sought to smooth over.

“The Sabbath is sacred to all Jews, Sadducees and Pharisees alike.”

“Of whom there are ten thousand in a land of a million souls.”

“We keep the law of Moses,” said Gamaliel, “the people follow.”

Suddenly, above the conversation, came the piercing trumpets summoning the faithful to prayer, and the ecstatic response of the Temple thousands crying: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

The three dignitaries paused long enough to make their obeisance to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. As they prayed, I looked out the window, letting my eyes roam from the courtyard, where the dead and injured were still being carried away, to the turrets of the Fortress Antonia, which rose high above the Temple walls.

“What does Pilate say of these murders in the Temple itself?”

Annas shrugged. “The Romans are a law unto themselves. They would lay waste to all Israel if it suited them.”

“The tetrarch Herod will surely protest the death of his Galileans.”

Gamaliel clucked his tongue. “Tiberius no longer listens. He enjoys the baths in Capri with his pubescent bedfellows. Sejanus rules unmolested.”

“Why else,” put in Caiaphas impatiently, “did Pilate attack these Galileans? He knew he could do so with impunity.”

“The Romans have only three thousand troops in all of Palestine,”

I pointed out, “and these are nearly all mercenaries, led by only a handful of Roman centurions.”

“The roads would soon be clogged with Roman troops from Syria and Egypt.”

“The Zealots have no fear of Rome.”

Annas favored me with his most syrupy smile. “We, for our part, are surprised at your company.”

“I am only surprised,” I replied, “that all of Israel hasn’t rallied to the Maccabean party.”

Gamaliel shook his head sadly. “Violence only begets violence, of which the Romans are past masters.”

“So be it. With the help of the Messiah, the nation shall be delivered. But while Roman soldiers man these ramparts there is no freedom.”

Annas stroked his long beard thoughtfully. “But first you must find the Messias. Is that not correct?”

“We will know him by his works.” My voice rose with emotion, as always, when I thought of our deliverer. “‘How beautiful he is,’ say the Prophets, ‘the Messiah King who shall arise from the House of Judah. He will gird up his loins and advance to do battle with his enemies and many kings shall be slain!’”

The Reb Gamaliel looked startled. “I see a different Messiah, born out of God’s love for his people, and hating no man. He is the Prince of Peace, the Wise Counselor foreseen by the prophet Isaiah and so many others.”

He recited softly from a half-forgotten psalm. “He will call the holy people together in justice. He will govern the sanctified tribes. No iniquity shall be allowed in them. And no wicked man shall remain in their midst. For God has made him strong in the spirit of holiness and rich in the shining gift of wisdom. How happy are they who shall live in this day, to see Israel rejoicing in the Assembly of the people.”

It was an innocuous homily.

“I see him as he must be to accomplish that for which he has come,” I retorted.

Gamaliel gave me a piercing glance. “Has it occurred to you, Judah-bar-Simon, that the Messiah you visualize is not sent to restore Israel to any temporal glory, but to redeem us from our sins? Is he not the Righteous One promised by Jeremiah?”

“It is all very clear that he comes to deliver Israel from foreign domination. As foretold by the prophet Daniel, he will make an end to our suffering as a nation.”

Gamaliel smiled wanly. “There is no greater prophet in Israel than Moses, for only he was permitted to see the face of the Lord. And in his promise of a Messiah he speaks of no warrior king.” The Reb’s eyes lifted heavenward and became dewy with emotion. “This was Moses’ promise to the twelve tribes in the desert: ‘The Lord thy God will raise up unto thee a prophet from the midst of thee, of thy brethren, like unto me.’”

“Did not Moses deliver his people from the Pharaohs?”

The Reb gave a small sigh. “Think as you will, Judah-bar-Simon, you cannot alter God’s plan one iota.”

I strove to curb my impatience. Were these old men so blind they could not see the truth, or so afraid to face reality, lest they be compelled to make a move that would risk their precious hides?

Annas sucked in his breath impatiently.

“He is all things to all people, this Messias, and for the sake of Israel we must put to rest all these rumors agitating our people.”

His cold eyes dwelt for a moment on his son-in-law. At his nod, Caiaphas turned to me uncertainly.

“The elders,” he said grudgingly, “have decided to entrust you with a very critical mission.”

I smiled incredulously. “Why, in all Judea, would the Temple choose a rebel like me for any mission?”

“Just because you are that man you speak of,” said the Reb Gamaliel. “The Pharisees and the Sadducees can agree, as you see, but the Zealots are irreconcilable.”

“We have nothing to do with either party. We stand for an independent Israel, free of burdensome masters of any stripe. And we have no sympathy for the fawning minions of Rome.”

Annas and his son-in-law, looking daggers, were about to turn on their heels, but Gamaliel stayed them with a detaining hand. His brown eyes probed deeply into mine, and he spoke more in sorrow than in anger.

“You do your father an injustice, Judah-bar-Simon. For he thought, as we do, that Israel must not be torn apart by warring factions if it is to survive.”

For a moment a shadow darkened my thoughts.

“What has my father to do with this?”

“If he were alive, he would instill in you a sense of the tradition in your family since David’s time. You are of this royal lineage, as you know.”

“Why else do I speak of deliverance, with one of my own as Master, not some grasping monster in Rome?”

Even though the room was bare, and the doors closed, the High Priests’ eyes darted about nervously. “Caution, young man,” Caiaphas cried, “there is some talk that even the Romans hearken to. Guard your tongue. Their Emperor is their God, and they will not have him blasphemed by such as we.”

“Such as we indeed.”

I had turned away an

grily, when Annas’ voice caught me at the door. “And if I would commission you to find this leader you speak of?”

I retraced my steps slowly.

“I would tell you that you are not the High Priest, nor the father of five High Priests, and that the river Jordan flows upstream.”

Annas permitted himself a ghost of a smile. “Listen closely. There is a man who calls himself a prophet, who lives like an animal in the Wilderness, with a camel skin for a robe and a loincloth for a tunic.”

I had moved insensibly closer.

“And what is he called?”

“The Baptist, because he purges men of their sins in the river Jordan.”

“And so our forefathers too used water for their purification ceremony.”

“He baptizes differently.”

“Who is this Baptist?”

“An Essene, we understand, a fanatical leader of a fanatical sect from the monastery’ at Qamram by the Dead Sea.”

I regarded the three men solemnly. “You must have some reason for wishing to know more about him.”

“There are reports that he heals the sick and comforts the poor with tales of a happy land beyond.”

I felt a tingle of expectation.

“And what, pray, is wrong with that?”

“If he were to limit himself to these harmless exercises, nothing. But he preaches that Jews should deny tribute to Rome, and drive out the tax collectors. This will not sit well with Pilate.”

“Or with the Temple treasury.”

I knew there must be more, for why else would they summon an outsider like myself?

He hesitated for only a moment, saying with a grimace: “His followers look on him as the true Messias.”

My intuition had served me well. “And is that not what all Israel is seeking?”

Annas shook his head grimly. “The nation must not suffer for the misdeeds of one man.”

“Do you seek a Messiah or a martyr?” I said in a voice harsh even to my ears.

Gamaliel’s hand stroked his untrimmed gray beard. “In this sad land of ours, Judah-bar-Simon, he could be both.” He sighed wearily. “Who knows what our future is?”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

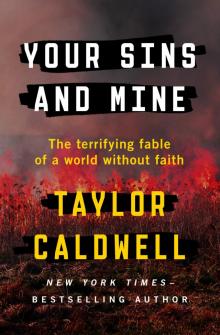

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine