- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

The Devil's Advocate Page 3

The Devil's Advocate Read online

Page 3

Dazed by pain and grief and anger, Andrew tried to remember what his father had told him. He tried to remember what he had been taught, by his father and his priest, of the long iniquity of Washington. There was 1945, when Russia had been hailed by Presidents and Generals as “our noble Ally.” That was after the second World War, was it not? Yes. And immediately after those days of war Washington had lent many millions of dollars to Russia, had “leased” her fleets of ships, had sent her millions of tons of food. Then there had been some sort of a Plan, which had sent countless billions of the American people’s money to Europe, for rehabilitation. The American people had been taxed into misery for this Plan, which had been used, to a great extent by the recipients, to arm Russia. The many other “noble” allies of America had done a fine and roaring business with Russia, especially those with Socialist governments. The atomic bomb had been presented to Russia by American spies who had had access to American secrets. All this had been done with full knowledge of its significance. Yes, with full knowledge of its significance!

Then, when the hour had come, Russia struck, not at her friends who had armed her with the money of the American people, but at America, herself. And in that hour, the “noble allies” had frantically declared themselves neutral, in spite of the United Nations.

But long before that time, Andrew’s father had told him, the degeneration of the American character had begun. All the violence of wars, all the cynical crimes committed against America, had been only the visible flowering of the innate disease which had long before devoured the strength of the American people. The car rolled on, in utter silence, and Andrew tried to remember. He was not only unconscious of James Christian beside him in the car, but of the Magistrate, the car itself, the people on the streets outside.

Yes, he remembered now. America had given up her freedom, which had made her strong and powerful and great, even before the second World War. She had watched that freedom erode, from the early thirties on, and she had done nothing. It had begun so casually, so easily, and with so many grandiloquent words. It had begun with a loathsome use of the word “security.” And in the name of that fantasy, that dream-filled myth, American pride, responsibility, grandeur and strength, had been systematically murdered.

What manner of men had lived in those days, far back in the thirties, who had so eagerly surrendered their sovereignty for a lie and a delusion? Why had they been so anxious to believe that any government could solve problems for them which had been pridefully solved, many times over, by their fathers? Had their characters become so weak and debased, so craven and so emasculated, that offers of government dole had become more important than their liberty and their humanity? Had they not known that power delegated to government becomes the club of tyrants? They must have known. They had their own history to remember, and the history of five thousand years. Yet, they had willingly and knowingly, with all this knowledge, declared themselves unfit to manage their own affairs and had placed their lives, which belonged to God only, in the hands of sinister men who had long plotted to enslave them, by wars, by “directives,” by “emergencies.” In the name of the American people, the American people had been made captive.

It was not the many wars, then, thought Andrew Durant, and the exigencies of those wars, which had made America captive. The wars grew out of the weakness of the people themselves, out of their disease and their fantasies. If they had not been mad in the very beginning there would have been no wars, for there would have been no tyrants raised up and supported with their own money and their own work. They would not have lent all their energies, their lives and their hopes, into the creation and then the demolishing of “enemies,” into the searching for new enemies after the last had been subjugated. They would not, finally, have become the slaves of an all-powerful government in Washington, slaves of a monster they had fabricated in their demented dreams.

Even when the Republican Party had been outlawed and declared “subversive,” the people had refused to see what there was to be seen. Even when the American Communist Party had suddenly joined forces with the party in power in Washington, and had supported it with shouts of joy, the people would not see. But it was too late, then. The disease had shown itself with all its fatal symptoms. The men with brave voices had been silenced, had been imprisoned, had been driven into exile, had been tormented to death.

But the disease which had stricken down the American people had stricken down Europe, also. The whole world was diseased, except for the South American nations. And they had made their continent an armed camp, their eyes watching America with mingled disgust, fear, and resolution. They knew that some of them were, even at this hour, being weighed and measured in Washington as potential “enemies.” America might be prostrate, hungry, desperate, filled with terror and despair. But she had always the strength for a new and maniacal war which would perpetuate her tyrants and prevent her people from revolting. All unions had been outlawed, many years ago. The people worked, staggering with exhaustion, in war factories, on the farms, for twelve hours a day, seven days a week, to maintain the gigantic war machine which the oppressors had created. They worked in numbness and in silence, like beasts.

Andrew looked at the speechless crowds on the sidewalks, and hated them. He thought of the Minute Men, who had dedicated their lives, and the lives of their families, to these hundreds of millions of animals who had lost, not only their minds, but their spirits. The Minute Men were like a few sane souls in one vast prison of madmen. They believed that sanity could be restored to this continent of murderers, bureaucrats, slaves, soldiers and robots. They believed that America could again be free.

But America was not worth the Minute Men, thought Andrew. She was not worth the life of a single one of them!

The Magistrate in the front of the car turned his head graciously, and asked: “Did you speak, Durant?”

I have only to say one word, thought Andrew, sweating and aching, and they’ll let me go. They’ll release Maria and the boys, and I could work for The Democracy. One word, a single word. What was this debased people that he should die for them, and his wife and children, also? Somewhere, he might find an island of peace, a refuge.

James Christian turned his head and looked at Andrew, and Andrew saw his face, calm, gentle and comforting, in the light of a dimmed street lamp. Andrew saw his eyes, strong and eloquent. Christian was a young man, too, and he, too, had a wife and children. He had looked at these faceless masses on the street, and he had not hated them. He had pitied them. He was prepared to die for them.

“Did you speak, Durant?” repeated the Magistrate, in an interested voice.

Andrew looked at the passing people. Now, here and there, he saw a head that was not bent, a face that did not move itself into an expression of submissiveness. A young face, a tired but thinking face, a brooding face. Only a few, but they were there.

“No, I didn’t speak,” said Durant. James Christian, beside him, sighed, and his shoulder touched his in understanding and consolation.

The black car crept up Fifth Avenue, weaving from side to side to avoid the holes in the pavement. Just ahead, Durant knew, were the ragged and unkempt fringes of Central Park, where, during the day, starved children listlessly played, desolated women crouched on broken benches, and derelicts of all sorts skulked, ate, and slept at night. Decades ago it had been a place of beauty and refreshment. Now it was little more than a refuse-filled jungle, dangerous by day and desperate from the first moment of darkness, its paths overgrown with weeds, hundreds of its trees dead, its ponds choked with old papers, broken branches and garbage.

At some signal which the prisoners did not catch, black curtains suddenly rolled across the car windows. Durant was startled from his somber revery by this. Why should their destination be hidden from him, and Christian, when within an hour or so they would both be dead? Involuntarily, he spoke: “Why did you do that?”

The Magistrate replied, tranquilly: “For obvious reasons.”

Then the car stopped. The doors were opened, and Durant saw the uniforms of the Picked Guards. The street outside was very dark and empty, though Picked Guards strolled, armed and alert, along the deserted sidewalks. Only a vague street light here and there showed the glint of guns; it was so silent that the footsteps of the Guards echoed back from the blank fronts of buildings. Durant and Christian tried to guess where they were, but it was an unfamiliar neighborhood. The big hands of the Guards reached in for them, and to Durant’s further confusion, the hands did not seize him roughly. The Magistrate said, in a low voice: “Careful. He has a broken arm.” Durant was then helped from the car with gingerly consideration. Christian was already on the walk, and now Durant could see his face, and his blank amazement. They both looked at the gloomy house before them, which was very closely guarded, and the sightless windows. A Guard held Durant’s uninjured arm, and helped him across the broken walk. Durant glanced at the Magistrate and the three strange men who had accompanied them, and they were smiling slightly. Then, the Magistrate leading, they went up the broken steps of the house, quickly and silently. A broad door opened, and Durant saw the Guards again, and the wide, high hall of what had once been a mansion. A dim blue light flickered from the plastered ceiling. Stumbling a little, and bemused, Durant saw the door shut swiftly behind them. A Guard opened an inner door, and the two prisoners were pushed, almost gently, into the sudden white blaze of what appeared to be a small operating room.

Two men, in the white uniforms of physicians, stood up at once. Dazed, the prisoners looked about them. They heard the door open again, and shut, and they were alone with the white-clad men, one of whom was elderly, and two Guards. An operating table stood in the center of the immaculate room, and there was a tank of anesthesia and the usual paraphernalia of a surgical clinic behind glass doors.

The doctors smiled at the prisoners, not professionally, but with friendliness. The younger lifted a chromium bottle and poured its yellow and sparkling contents into two glasses. Bewildered, the prisoners took them. “Drink it,” said the older doctor, nodding his head. “It’ll refresh you.”

Durant stared at the operating table. Diabolical means of torture? That did not matter, either. There was a limit to human capacity. The two prisoners drank the liquid; it was strong and almost hot on their tongues and in their throats. Instantly, a sense of invigoration came to them.

“Sit down, please,” said the older doctor, all briskness. He picked up a pair of scissors, and while Durant watched him, stupefied, he gently cut away the clothing from the broken arm. Now it was exposed, in all its swollen and purple injury. The doctor frowned, shook his head. He nodded to the Guards, who lifted Durant to the operating table, and then forced him into a lying position. The younger doctor was examining Christian’s wounds very carefully.

The older doctor motioned to a Guard, who instantly clapped a mask over Durant’s face. He struggled against it, pushing it aside with his left hand. His hand was caught. For one moment he stared up at the face of the doctor. “What?” he cried. The doctor said reasonably: “How are we going to set that arm without an anesthetic? Or would you rather I do it the hard way?” The mask was firmly placed over Durant’s face again, and he was at once choked by the fumes of some rapid gas. His senses floated off into warm darkness, in which sparkled one brilliant star of disembodied pain.

He began to dream. He dreamt that Maria was standing over him, kissing him and weeping; he dreamt that he heard the voices of his children. He felt the touch of Maria’s hand on his cheek, the warmth of her hair on his face. Then, abruptly, she and the children were gone, and loud sounds battered against his ears, confused sounds as of great voices. They subsided to a murmur, and he opened his eyes.

He was still lying on the operating table, but the pain in his arm had gone. Through a mist, he saw that it had been splinted and bound. There was a prick in the flesh of his left arm, and the mists melted away, and he felt a surge of well-being and strength. He looked for Christian, who was well patched, and sitting near by. A Guard helped Durant to a sitting position, and he saw the smiling faces of the doctors and the Guards.

“Feeling better now?” asked the older doctor. Durant could not reply. He was helped off the operating table, and to his greater astonishment, he discovered that the anesthetic had left no effect on him. A Guard was opening a rear door, and he motioned to the prisoners with his head. More and more astounded, Durant hesitated, put his hand to his face. It was wet, and then he remembered his dream. Trembling, he followed Christian into the next room, which was white and bare, and contained only a table and some chairs. On that table was set a tureen of steaming soup, coffee, bread and butter, and some cold slices of meat. The Guard said: “You have half an hour.”

The prisoners fumbled for chairs, and, stupefied, looked at each other. The Guard repeated, patiently: “Half an hour. And no talking, please.” Durant turned to him abruptly. The Guard’s face was large and quiet and noncommittal. Durant then looked at the table. Christian was ladling soup into a bowl for him, and the other man awkwardly picked up a spoon with his left hand. All at once they both discovered that they were extremely hungry, and they began to eat with ravenous haste.

The Guard watched them eat, thoughtfully. He saw the two men exchanging eloquent and bewildered glances. He hooked his fingers in his belt and moved restlessly. He asked: “How is the arm? Better?”

Durant turned to him again, and asked rapidly: “Why was it set? Why are we being fed?”

The Guard smiled. “You have ten minutes more,” he said. For the first time Durant noticed his voice, strong and interested, and even sympathetic. The Guard came to the table and lifted the heavy pot of coffee and carefully poured the hot brown liquid into the mugs. “Five dollars a pound,” he said, reflectively. “When did you last drink real coffee?”

In his stupefaction, Durant could find nothing to say. Then it came to him that this was the part of the plot. He was to be reassured, he and Christian, and led into some trap. He frowned at his friend, and shook his head warningly, and lifted the mug to his lips. The taste was delightful to him, recalling childish memories of his father’s house, and his mother’s kitchen. His father, who had probably been murdered, his mother who had died of grief! He put down the mug, and for the first time tears came into his eyes. He saw Christian regarding him sadly.

“Time’s up,” said the Guard briskly. He opened a door and the prisoners saw the hall again, outside. They followed the Guard into the hall, and then to its rear. The Guard flung open a door, and there before the two men was what had originally been the drawing room of the mansion, lofty, high-ceilinged, intensely lighted and warm. But all windows had been removed, and instead there was a whisper of warmed fresh air circulating through ducts.

There was a dais like a speaker’s stand at the end of the room, and below it a long table and a number of chairs. Behind the dais stood two great flags.

“Look!” cried Durant, stopping suddenly on the threshold and pointing with an agitated hand. Christian cried out, also, and then they stood, staring, unable to believe. For one of the flags was the old lost flag of the United States of America, rippling in all its ancient splendor of red and white bars and shining stars, the old flag which had been abolished twenty years ago in favor of the debased rag of The Democracy of America, bloody of background and having on it only one bloated white star. At a little lower level, gently fluttering, stood the flag of the Minute Men, white background, blue shield on which was imposed a snowy crescent moon above two cro

ssed rifles.

The two prisoners, after their first exclamations, stood petrified and unbearably agitated. The Guard passed them and drew out two chairs from the table. “Sit down,” he suggested. Stumbling, their eyes still fixed on the flags, the prisoners went to the seats. Then the Guard moved to the single door and stood there, looking at the flags also.

A trap? Durant turned impetuously to Chrisitian and could not restrain his voice: “The flags! What are they doing here? Where are we? What is all this?”

Christian said thoughtfully: “I think I am beginning to see. But why did they kill our eight friends?”

Durant moved his splinted arm a little. “Why did they set this? Yes, why did they kill all those—” He shook his head over and over. “It must be a trap.”

“For whom?” asked Christian. “Not for us, surely. They knew we’d never speak.”

“They think we will,” said Durant grimly, “with this masquerade.” He again fixed his eyes on the flags and all at once something broke in him with unbearable pain. The flag of the United States of America, destroyed as completely as the Constitution had been destroyed and defamed and befouled! It fluttered in a fresh blow of air from the ducts, and seemed to lift itself proudly, a thing which lived, a thing which had not been killed after all, in spite of the edict which had made it a grave criminal offense to have even a photograph of it in one’s possession. How many children knew there had once been such a flag over a free nation? How many tens of thousands, yes, millions, of young men had died under the monstrous flag of The Democracy of America, and had never known these bars, these wonderful stars, this flow of shining color and majesty? Durant’s head dropped on his chest, and his black eyes became blinded with tears.

He heard the door open and several men, headed by the Magistrate, entered the room silently, and without a glance at the prisoners. Durant heard their quiet footsteps but did not raise his head. Then he heard Christian exclaim in a muffled voice: “Look! It isn’t possible.”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

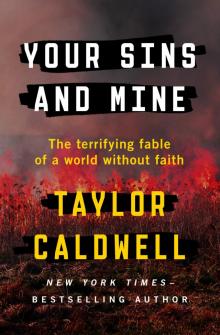

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine