- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

Testimony of Two Men Page 9

Testimony of Two Men Read online

Page 9

The moment she was certain that her son had left, Mrs. Morgan briskly put aside her canes and moved smartly to the windows to look down on the town. The sidewalks were gleaming with moisture in the dusk. Umbrellas moved in a solid phalanx below, and the gaslights were lit, surrounded by auras of dull and streaming yellow in the rain. But the lamps were scattered, and it was very quiet. Horrid little town. Her Robert would soon tire of it, and then they'd return to civilization, in Philadelphia. Well, she'd see. She'd have tea with that woman tomorrow and let her know that Mrs. Morgan was condescending to her, she the mother of a murderer.

"I really cannot force myself to eat anything," she complained to Robert when the table was laid in her suite and the savory food set before her.

"Oh, that's too bad," said Robert, taking up his soup spoon with enthusiasm. "This is very tasty. Do try a sip."

She ate a very hearty dinner, even more than Robert, and complained and sighed and murmured dolorously all through it. As a thrifty woman she deftly tucked two buttered rolls into her handkerchief for later nibbling. After all, she told herself, she slept badly. And waste was sinful. It had been paid for. It didn't do to encourage gorging in servants, who were allowed leftovers. "Two dollars for this dinner, Robert? Do they think you are a millionaire?"

CHAPTER SIX

"An odious woman, really," said Marjorie Ferrier to her son two days later. "So affected. She spent most of tea-time preening and condescending and bragging genteelly and talking in what she doubtlessly considered a very 'refined' way. How could such a nice gentlemanly boy like young Robert have such a mother?"

"And how could such a nice mother like you have such odious sons?" Jonathan asked her. "It's all inheritance from distant ancestors."

"My sons are not odious," said Marjorie. "Here, dear, do try this English marmalade. You aren't eating very well these days. What a wonderful morning! It's bright and warm again. I think I'll work in the rose garden. Where are you going now, Jon?"

"Taking young Galahad on the rounds, as usual. I want to be sure—"

"Of what, dear?"

"It doesn't matter. Nothing matters any longer."

But everything always mattered too much for you, my son, thought Marjorie with a sigh, as her son gave her a brief kiss and left. She clenched her slight hands on her knees and closed her fine hazel eyes. Would there never be an answer to her prayers? How could she live alone here, in this big house, without Jon? All her dreams had come to nothing. There were no grandchildren, there was no happy laughter anywhere. There was no gay coming here any longer, as once there was, when Mavis was alive and Jon was busy. Jon? She thought about it. When had he stopped smiling that quick dark smile of his? A year after he had married Mavis? Two years? Three? He had stopped within six months.

Oh, God, thought Marjorie, if only Mavis had never been born! If only Jon had never seen her! If only she had died at birth! But life, it seemed, was tragically made up of "if onlys."

She knew it was best for Jonathan to leave Hambledon and never return, but her opinion was not based on his nor those who knew him. There were times when she felt she could not wait for him to go—for every day was a day of danger and impending terror, and pretense.

"This is a fine new rig you have," said Jonathan to Robert Morgan. "Good horse, too. When did you buy it?"

"Yesterday." Robert gave him a sunny smile. "Like it? I do, too. I heard the horse had been sired by one of your own. My mother was upset."

"Why?"

"The expense. She thought I should hire a buggy for a while, instead of buying one. I don't think she's joyful over this town. Besides, Mother is very—well, I suppose you'd call it financially discreet. I told you, you'll remember, that my father didn't have much money of his own; he did a lot of charity work; too much, according to Mother. What we have belongs to Mother. Of course, I'm her only heir, but sometimes it makes things difficult."

"Well, widows have to be providential," said Jonathan.

"I'm hardly a profligate son," said Robert. "I worked in drugstores when I wasn't in school, and mother told all her friends that she didn't consider it very 'nice' but that I was an independent boy and I had insisted. The truth is, Mama was always very near with the cash; thought if I didn't have any, I'd not get entangled with females, or something. I had to have more than the two dollars a week she gave me when I was in college—so I worked. Waited on tables and such. A lot of the fellows looked down on me for that, though their parents didn't have half the money Mama has. Dear Mama."

"Where'd you get the money from to buy this outfit, then?"

Robert laughed and proudly held the reins. "I charged it to my mother. She'll get the bill soon. The funny thing about it is that she never asked me how I bought it, acting on the principle that if she did not ask, there'd be no bill and no unpleasantness."

"You'll soon have plenty of money of your own, once you're established here," said Jonathan. "I've shown you my rates; don't come down on them. They're a Utile higher than average, but then you're an authentic doctor and not a quack. There's something else I've wanted to talk to you about. When I was a kid, most doctors had only the most elementary medical educations, having merely studied under physicians and gone the rounds with them for two or three years, and reading their medical books. They did a lot of God-awful damage, of course, but a lot of them did a lot of good. They developed, or were born with, a 'smell.' They could smell out illnesses on merely entering a room and could make a prompt and accurate diagnosis on the spot. A sort of sixth sense. Every real doctor has that, even in these days of 'scientific diagnosis,' but it's not held in good repute any longer. The more we begin to rely strictly on laboratory findings, the more dull hacks—though out of good medical schools—we'll find ourselves afflicted with, and any man with well-off parents can aspire to be a physician, whether he's fit for it or not. Just for the prestige. Potential carpenters and blacksmiths in operating rooms.

"Don't take the corners too fast with this horse. I had his dam, too, and she had a way of cutting around. Well. I'm not against full laboratory procedures; I do a lot of it, myself. Stops the guesswork. But we can have too much of it; I've seen some tragic errors when doctors go by the laboratory and not by common sense and careful, personal diagnoses. Of course the hacks couldn't practice medicine any other way if we didn't have laboratories these days, so perhaps many lives are saved. But nothing beats an eye, an ear, and a sense of smell, that sixth sense I've been telling you about"

"And you're afraid I might not have it?"

"We'll see. Beginning today. Even if you don't and are careful, and lean heavily on the laboratories, you can't do much harm. Now, when I was a boy, we knew a physician in a tall silk hat, stock, chains, and the usual frock coat and striped trousers and spats and a gold-headed cane. Almost illiterate. Big bearded bastard with a voice like an organ chord. He'd 'studied medicine' under another just like himself. Impressive old fart. And yet, I've never met a more acute diagnostician and never a man, even a modern physician, who could cure faster.

"I used to have what they called a 'chest' in those days. I stank up every classroom with the bag of camphor my mother hung about my neck, and I reeked with asafetida, too. That's what really made me a good boxer. I had to be. Then there was goose grease, steeping feet in hot water and big doses of castor oil. I was supposed to sweat it out. Well, one winter my chest was worse than usual, and our family doctor had influenza, and we called in Dr. Bogus. He walked into the bedroom where I was coughing my lungs out, sniffed around the room, said 'Ah,' came to the bed, looked up my nose and down my throat, and said, 'Where's the cat?'

"Now, we always had cats in the house, two or three at least. Love the beasts; still do. My mother was surprised, but I hauled under the bed and brought up my favorite pussy. There's the villain, or villainess,' said Dr. Bogus, and picked up pussy and gently threw her out of the room. It seems I was sensitive to cats, but no one had ever suggested it before. I have them still, on the farms, but not in t

he house. And I still get a 'chest' if I go into a house where a pussy is in residence. Everybody laughed at Dr. Bogus, but he was right, you see. And everybody who laughed still called him in emergencies when real doctors were baffled. He had a nose."

"We can diagnose sensitiveness to animals, or whatever, without having a nose now."

"True. What are they beginning to call it now? Allergies. They're still mysterious. Why does one man drop dead if he takes an egg and another can have half a dozen of them for breakfast and feel 'fine,' as Teddy Roosevelt calls it Sickening word. No one knows exactly why some proteins can kill some people and not affect others. Allergens, they call them these days. But why? We still don't know. Dr. Bogus didn't know either; he'd never heard of allergies to the day he died. But he knew they existed, just as Aristotle knew the nature of an atom even though he'd never known any scientific instruments. And today our scientists are talking about 'the atom' as if no one had ever proposed the theory before or written down a hypothesis. Dr. Bogus, I bet could outdo any of your teachers at Johns Hopkins when it came to a diagnosis, even if he could rarely pronounce the name of the disease correctly and didn't know Latin from Sanskrit He could lay his ear for a second to a man's chest and look into his eyes and come up with the exact thing that ailed his heart. And his weird concoctions, witch-doctor stuff, really, which he whipped up in his dirty little pharmacy, had almost magic qualities, though I doubt he knew what the hell most of the ingredients honestly were, or how or why they worked."

"My father told me about men like that," said Robert with doubt. "Me, I'm the real laboratory diagnostician."

But Jonathan did not laugh. He said, "That's not enough. I expect more from you than that. That's why I picked you over the others."

"Thanks," said Robert.

"The others," said Jonathan, "were strictly scientific chaps. That's not enough. We're going to St. Hilda's first. There're a couple of cases or so, that I want you to diagnose."

"By my sixth sense?"

"By your sixth sense. You strike me as a real doctor; I don't want to be disappointed. Take Leonardo da Vinci. He designed submarines and was laughed at for centuries. But now we not only know, because of him, that they are possible, but we are beginning to design them, too. He designed flying-machines, and now we have men working on such things, and, frankly, I'm afraid of them. The faster we get into communication with our fellows, the faster we'll learn to hate them. The sentimental used to carol that the telephone, by making instant communication possible, would clear up all misunderstandings and foster a spirit of brotherly love. Instead of that it has become an instrument of invasion; anyone can invade your house if you have a telephone, and most of the time it's a lot of nonsense. And a lot of the time you resent the caller and start to hate his guts. Science is going to make the new world a pretty threatening place."

"Antiprogress, I see."

"Don't laugh so smugly, boy. The more weapons you give a man, the more dangerous he becomes, and science is just on the threshold of supplying mankind with really big weapons. Most of them impersonal. When men fought hand-to-hand in battle, it gave them some respect for life, even if they killed in the name of whatever. But a rifle and a cannon— they are only instruments of destruction and you never see the man you murdered, so how can you respect his manhood? Watch that corner. It's pretty busy."

The streets simmered with the warm June sun and the lawns danced with the shadows of the great old trees. Children were racing to school, swinging their books on straps, little boys in knickerbockers, little girls in bright summer cottons and with ribbons in their hair. Small towns, thought Robert, masterfully handling the reins, have a lot to commend them. There's a certain close quality about them, a sense of nearness. He said, "I don't think that isolating oneself is the best way to get along with others."

"But it's a lot safer," said Jonathan. "Besides, who wants their affection? That's cheap and common, as my mother would call it. Give me respect anytime. An island is better than an anthill. One of these days well run out of islands, of any kind, and you'll see the heartiest massacres of whole populations. If you live long enough, and pray you don't. Man just can't stand too much of his fellowman."

"You're making me melancholy."

"Melancholy was highly esteemed by the Greeks. Don't underestimate it. Did you ever see a fool who was depressed, really depressed? No. Melancholy, and all the other mental ills, seem the prerogative of the intelligent. You've got to know the world to conclude you can't stand it."

Robert hesitated. "May I ask you a personal question? Thanks. Were you such a misanthrope before your—your— trouble?"

"You mean before I was on trial for killing my wife and child? Well, don't use euphemisms. Yes, I think I was always a misanthrope to some extent. If you aren't one yet, I advise you to cultivate misanthropy. Then nobody will catch you flat-footed, no one will cheat you, no one will stick a knife in your back. You'll always be looking for such things and you'll never be disappointed. But you'll be forewarned, and that's a blessed thing."

School bells were ringing, and churches were chiming nine o'clock; distant dogs barked lazily. A water wagon was roaming slowly along the streets, wetting down the gutters and making little black rivers among the cobblestones. A scent of moistened dust rose in the air pleasantly, and from somewhere came the passionately sweet scent of a linden tree. And always, over it all, the fragrance of garden roses, hot with life under the sun. So peaceful, thought Robert.

"The thing we have to learn, all of us now, is that peace is on the way out as a condition of existence," said Jonathan. "How do I know? I get the London Times. Parliament is expressing its 'distress' that Germany is crowding the British out of what they call their 'traditional markets.'"

"So?"

"Now, what the hell did men ever fight for, in all the history of the world, except for markets and new territories? And a right to exploit? Or money? All the high-sounding things don't mean a damn. Our own Civil War, as Lincoln himself explained it, was not to free slaves but to preserve the Union, and he wanted to preserve the Union because he knew that two weak divided countries where once there was one strong one would be an invitation to European adventurers. Why our own Revolution? The old boys considered themselves 'loyal subjects of His Majesty,' almost to the last. They just rightfully resented having their money—their money, you will observe—being taken away from them in taxes for the old country's benefit. There can be no freedom without private property, and money is private property, and that's what we fought for—the right to our property, which meant our liberty. That's why I say now that I was never so alarmed before as when hearing the British Parliament express itself, in its gentlemanly way, as being 'distressed' over bustling Germany's vigorous invasion of British foreign markets. I'm scared to death."

Robert could not imagine Jonathan Ferrier being "scared to death" over anything. He remembered the accounts in the newspapers of Jonathan's disdain of both judge and jury, his black impatience, his gloomy contempt. Yet, his fife had been in the hands of those men; he had not feared them at all.

"Here we are. 'Jewel-like St. Hilda's,' as some lady once called it."

They had arrived at the somewhat elaborate wrought-iron gates of the small hospital. Beyond were wide gravel drives and handsome lawns and elms and neat flower beds and benches for convalescents. The hospital itself was of slurring white brick with red chimneys and blue-shuttered windows and even curtains against the glass of the expensive private rooms. It resembled some great English mansion and not a hospital at all. Some nurses in white were guiding patients over the grass or wheeling them in chairs, and everything sparkled freshly and someone was cutting grass and the fragrance was delicious on the warm air.

"Well, it looks as a hospital should look, and not a barracks," said Robert. A man came running, as they drove up to the white steps, and caught the horse's bridle. The two doctors jumped to the ground and they entered the hospital through doors opened wide to the fresh breeze and

the odor of growing things. It was cool and light inside, the inlaid linoleum polished on every one of its yellow squares, and the hall was lined with comfortable chairs and tables. A nurse at a desk looked up, saw Jonathan; her face closed. She said, "Good morning, Dr. Ferrier. And Dr. Morgan."

The hospital was four stories high and very hushed; the corridors, in spite of Jonathan's protest, richly carpeted, After all, he was told, the patients who could afford St. Hilda's had delicate sensibilities and they could not endure clacking noise. "And the hell with being sanitary," Jonathan had told Robert. "It's a wonder they didn't carpet the operating rooms, too, and the water closets. A lot of the more costly rooms do have rugs in them; there're still a lot of pompous quacks who don't believe in germs, or, if forced to look at them through microscopes, murmur that they're 'interesting little creatures.'"

The very few patients whom he had recently accepted— and who had believed in him in the blackest of times—were on the second floor. So the two young men walked up the wide white-painted stairs, which wound up to the top in a graceful spiral. The hospital hummed with a soft busyness; nurses passed them or approached them; doctors with bags stopped to gossip to each other. Jonathan ignored them all, even those who tentatively greeted him. Robert was embarrassed. He knew a few of the doctors now and when they spoke to him pleasantly, glancing furtively at the silent Jonathan, he replied with a little too much effusiveness. His bag felt hot in his hand.

Jonathan swung open a broad door into a big and comfortable room full of sun. His manner changed at once. "Well, how are we this morning, Martha?"

A little girl, not more than ten, was listlessly lying on heaped pillows, her fair hair streaming about her shoulders. Robert had not seen her before. Jonathan took up her chart from the white dresser, glanced over it swiftly, frowned. "This is Martha Best," he said to Robert. "The daughter of one of my closest friends, Howard Best, a lawyer. In fact, I'm her godfather. Aren't I, Martha?" His face had become gentle for all its darkness, and he went to the child and bent and kissed her cheek. She caught his hand, her blue eyes fixed anxiously on him.

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

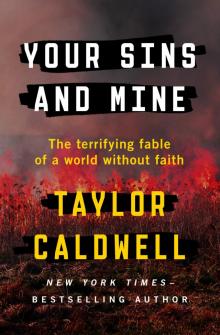

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine