- Home

- Taylor Caldwell

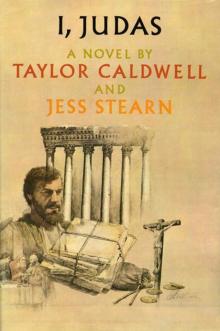

I, Judas Page 5

I, Judas Read online

Page 5

The floor was so thick with people that it took me a little while to find a place in the front. The speaker’s eyes rested on me for a moment, and I detected a smile. But how could that be? I had never seen this brawny giant of a man before. But then, suddenly, the robe he wore became the cuirass of a Temple guard, and recognition dawned. Of course I had seen him before. He was the Levite who earlier in the day had threatened the whiskey-monger. No wonder they knew me. They were everywhere.

I soon learned his name, for a man, vaguely familiar, with the face of a hawk and the mane of a lion, stood up boldly and said: “Simon Zelotes, I respect you as the leader of the Zealots and agree that this is not the Rome of the Republic, but it is still Rome. Anyone who thinks it will crunch like a rotten apple at the first bite will hang upside down for his mistake.”

I would hardly have known this man, his dress and bearing were so changed. But his name soon confirmed who he was and the game they had played between them for my benefit.

“Well said, Joshua-bar-Abbas,” replied Simon Zelotes, “but rest assured there will be no half-hearted assault on the Empire. Nothing of importance will be done until the time is ripe. But we can prepare ourselves for that time, establishing arsenals at every ambush point on the Empire lifeline from Egypt to Syria.”

Joshua-bar-Abbas looked at him doubtfully.

“With all respect to you, Simon Zelotes, and to myself, we need a leader to inflame the people and stir their imagination.”

“True,” said Simon, “and that can only be one man.”

There was a quickened awareness in the crowd, and shouts of “Hosanna, hosanna, to the Messiah, the Deliverer of Israel.”

I felt a surge of excitement in finding others who felt as I did. But still I disagreed, for I had seen in Rome the sullen faces of a slave population that outnumbered their masters, and I knew that the right spark would start the conflagration that would consume this evil whore.

Not all there were Zealots; some were simply sincere patriots concerned about an Israel straying from its fathers. An old man stood up, and I recognized him with surprise. This was Nicodemus, a liberal Pharisee like Gamaliel, whom some considered the richest man in Israel. He was no Zealot and made no pretense of it. “My only interest,” said he in a slow but resolute voice, “is that Israel survive as the land of the Chosen. I walk the streets of Jerusalem and am dismayed to see how things change. Our young men are becoming Romanized. They dress like Romans, and strut like Romans. They enter the gymnasiums, patronize the arenas, and dream of becoming Roman citizens. Some have had themselves uncircumcised because the Romans find this custom offensive. Our daughters fraternize with the conquerors and intermarry, leaving their traditional worship. It is a sad state of affairs.”

“And how,” asked Simon, “would you turn this about without violence?” It was well known that Nicodemus counseled caution in all matters for fear of Roman reprisals.

“I am an old man,” said Nicodemus, “and I have seen much of life. I, too, have seen a decline in the Roman character which can only lead to their ruination.”

“And how,” asked the fiery Joshua-bar-Abbas, “do we know at what point the character of a people weakens? It is not like a man who deteriorates through his thoughts and actions before your very eyes.”

“When they give over to government,” said Nicodemus, “those duties which they should be pleased to perform themselves. When they are told they will be fed and sheltered even when they won’t work, when they are promised security from the cradle to the grave, when they are told the state will take over the supervision of their children and say what schooling they should receive and where. When they are told all these things and supinely accept them.”

Joshua-bar-Abbas shook his head fiercely. “I have not an old man’s patience.”

“Give it time,” urged Nicodemus. “We cannot consider our fate without considering Rome’s. In this Rome there is no Cato the Censor, no Marcellus who put his own son to death to preserve the principle of duty first to the state. There is only a corrupting greed that I have seen with my own eyes. Greed for power and for the luxuries it brings, for fine homes and furnishings, for great estates and licentious sport with wine and women. All the seeds of decay are there. The citizens of the greatest power on earth have come to prefer idleness and games to work. Rome will fall of itself to the first positive idea that comes along. I promise you that.”

Nicodemus believed that socio-economics ultimately determined the fate of nations. “There is a decline in the Roman family that bodes ill for Roman vitality. Only the baseborn and slaves indulge in large families, which they know the state will support. The middle and upper classes so often do not marry and make a business of abortion. Soon there will be nobody to support the hordes who are born slave and stay slave, happy to be fed and entertained, and occasionally to fill their pockets with excursions into dark alleys, preying on the very people who support them.”

Joshua-bar-Abbas was not impressed.

“All that Nicodemus says may be correct, but we cannot wait for Rome to complete its decline. By that time the change will be so great in Israel that our sons and daughters will be Roman and declining as well.”

There was some laughter at this sally, and even Nicodemus smiled good-naturedly. “I counsel patience for the sake of us all. First let the Messiah arrive and decide how Israel shall be saved.”

The meeting was not going well. Many were beginning to look around restlessly. I rose to my feet.

“May I say a few words?”

Simon Zelotes held out his arms. “Here is a young man,” said he, “who could live in luxury but who has cast his lot with us. Speak, Judah.”

I had never spoken publicly before, but my mind was clear and precise. I could pick out faces in the crowd and sense their quickened interest. I wasted no words.

“In the beginning,” I said, “the Maccabeans were a handful, fewer than we. But they had purpose and faith. ‘Many,’ observed Judah the Maccabean, ‘can be overpowered by the few. Victory does not depend on numbers. Strength comes from heaven alone.’”

I could see Nicodemus’ long face break into the semblance of a smile. But Cestus stood stolidly, his arms folded, and the younger Zealots sat quietly.

“The Maccabeans were not a warrior people. They were farmers like many of you. They tended sheep and goats and cattle, minded their pigeons and tilled their fields. They were a peaceful but also a freedom-loving people. The Jews in that time would not do anything on the Sabbath. Antiochus and his Syrian Greeks rejoiced in their holiness and celebrated their Sabbath by massacring them by the thousands in their caves. Only when ordered to worship idols did the Jews finally resist.”

My voice rose. “But when they were ready, a leader came in answer to their prayers.”

I had the audience in my hand now.

“Mattathias the Hasmonean was rich in sons. John and Simon, Judah, Eleazar, and Jonathan. They banded together with friends and neighbors, attacking when the enemy least expected. They harried him constantly, raiding his caravans, pillaging his arsenals, picking off stragglers. They fought not only on the Sabbath but on the Day of Atonement, and every other day as well. In a pitched battle, on the plains of Emmaus, the mercenary army of the Syrians fled at the first assault. Their heart was not in the fight. With each victory, the Maccabees”—I held up my sleeve to show the emblem—“the Hammerers of the Lord, gained new followers. But they were still outnumbered. At Elasa, Judah, facing a vastly superior force, told his tiny band: ‘It is not hard to die, if one dies for freedom.’ And he was right.

“In the end, Judah retook Jerusalem with an army of a hundred twenty thousand soldiers, enough to liberate any people.” My eyes traveled over the silent crowd. “And it shall be done now as it was then. God has not abandoned us. He will send us the Messiah, and our enemies will be as chaff before him.”

This was what the crowd wanted to hear, and they reacted warmly, voicing their approbation as though ever

y success of the Maccabeans were mine. It was nice to know that one could so easily stir others by appealing to their desires.

But not all were so easily swayed. Nicodemus’ long face appeared to have grown longer.

“The Romans,” he said drily, “would hardly agree to the description of themselves as chaff.”

Knowing I had the crowd with me, I rejoined boldly: “Does Nicodemus imply that the Messiah sent by God will not have power to deliver Israel from any adversary?”

He stroked his chin thoughtfully, not the least abashed.

“First we must know he is the Messiah, and then he must know it as well.”

“Of course he will know it. How else can he lead us?”

“True, but he may march to a beat different from ours.”

Offended by what they considered nit-picking, the younger Zealots began stamping with their feet and shouting: “Down with the unbeliever.”

Nicodemus’ eyes flashed. “I am a believer,” he said quietly, “or I would not be here. I stand for any cause that will prepare the way for the Deliverer of our people. And I will support any cause that I believe in.”

This last, of course, was a telling blow, for money was badly needed to support the projected uprising, and Nicodemus, the wealthiest merchant in Palestine, was not one to be sneezed at.

Joshua-bar-Abbas held up his hand. “Nicodemus, as a friend of freedom, is entitled to his say.”

I saw a flaw in Nicodemus’ argument. “In the slave population lie the seeds of many revolts. They outnumber their Roman masters by far, and would likely join any uprising.”

He did not agree. “They have no spirit, or they would have risen long before. These are not the gladiators who fought with Spartacus up and down Italy, but household parasites so long provided for that they no longer care for anything but free food and shelter. You will have to look elsewhere for support. It will not come from the mean-spirited.”

In my heart I knew he spoke the truth.

“Then it will come from the brave in heart,” I responded in ringing tones, “from those who lead the legions against enemies they do not hate, from taxpayers who wince under every crushing new demand, from fighters everywhere for the cause of freedom. Nobody loves the tyrant, nay, not even the Romans. What happened to Julius Caesar could happen to lesser than he.”

“For every fallen Caesar, ten will rise,” said Nicodemus.

“But they will not be sent by God and have God’s unlimited power. Does not the Scripture say that when he comes all nations will make obeisance to him? Does Nicodemus question the Prophets? Certainly, he is not a materialistic Sadducee blinded by his wealth into thinking there is nothing before and after.”

“The Zealots and the Pharisees have no quarrel, except in the matter of zeal. You know that, Judah, for there was no more distinguished Pharisee and patriot than your father.”

“I know that the time has come to resist. It has been two hundred years since the Maccabeans gave us freedom, and a hundred years since the Romans took it away. A hundred years of Rome is enough, I say, enough of Tiberius, who would rid us of our customs, enough of Sejanus, who hates Jews because they speak for freedom, enough of Pontius Pilate, who would make of Israel a footstool for his own petty ambitions. I say to God, dear Lord, reveal to us the Promised One, and we your loyal servants will do the rest.”

Again I showed the hidden emblem. “Let us look to the day,” I shouted, “when this stands not only for the Maccabeans but for the New Deliverer, the Messiah, who is already here and waiting. This I know, for the time is ripe, and this the whole world wall one day know.”

I sat down amid deafening applause. Even the grim Cestus found cause to smile. As for Nicodemus, what did it matter that he frowned and seemed troubled? He was an old man, and the old forever counsel patience, when it is impatience, the refusal to accept the inevitable, that brings about the miraculous changes that give life its flavor. I would rather die a thousand deaths than live one life a slave.

With one speech I suddenly found myself a leader among the Zealots. Previously, I had not made any significant contribution, listening as others talked and planned.

Cestus and Joshua-bar-Abbas now wrung my hand.

“You have given us a splendid idea,” said Cestus with a grin that split his ferocious face.

“I am gratified,” said I, looking my pleasure.

“Until we are strong enough to take the field, we shall do as the Maccabeans. We shall loot their arsenals and ambush their caravans until the Romans no longer brag that their highways are as safe as the Forum at noon.”

I remembered what Annas had said about the lifeline of the Empire from Alexandria to Damascus.

“They will not take this lying down.”

Cestus had been joined by the Idumean Dysmas, a sentry just relieved of duty.

“By the time they know their adversary we will have an armed force, fully supplied, stronger than anything they can bring against us.” He laughed mirthlessly. “They already have their hands full with the barbarians in Germany, the tree-climbing Britons, and the Parthians.”

“And what of a leader? Without the Messiah there is no hope for a general uprising. All wait for the Deliverer and will not be delivered without him.”

Bar-Abbas chuckled in his scraggly beard.

“If we do not find a Messiah, we will manufacture one.”

Chapter Three

THE BAPTIST

I KNEW HIM AT ONCE.

He was standing knee deep in the muddy waters of the Jordan, his hand on a young man whose dark head was bowed in resignation.

“Repent, and be cured,” he cried in a voice that carried beyond the shore.

The youth, with an effort, lifted up an arm, and it was withered, the fingers cramped and deformed.

The Baptist, it could have been no other, passed his hand briefly over the afflicted arm. “Pray to the Father, who can do all things, even to moving mountains.” His voice held a vibration which seemed to send out a current of energy. I could feel it where I stood, and so did the youth. “I feel the heat,” he cried.

“You are open,” said John, “that is well.”

I had never witnessed a healing and had no faith in them. How could anybody heal that which defied the finest physicians? It seemed a silly superstition, but the mind did wondrous things. Believing something was often the next step to the thing itself. How many swore they had seen Simon the Magician grow wings and fly, and yet he was only a conjurer duping the gullible?

But with my own eyes now I witnessed a miracle. It could have been nothing else. The arm had been paralyzed, and now, incredibly, the shriveled skin began to smooth and the muscles took shape.

“In the name of the Lord God,” boomed the Baptist, “Azriel, the son of Hammon, is made whole.” The young man uttered a cry of jubilation, raising his restored arm for all to see. A sound that began as a murmur grew to a crescendo. The lame, the halt, and the blind in the marveling throng fell to their knees and shouted: “Hosanna!”

“He must surely be the Messiah,” said an old woman with a cane. “Only the Anointed of God can do these things.”

The Baptist seemed unmoved by the crowd. He stood the youth straight in the water, cupped his own hand in the swirling river, and doused the youth’s bare head with the water.

“Love God and be purified,” he said. His eyes were directed at the young man. Nobody else existed for him in that moment. “I baptize you Isaiah, which means the salvation of the Lord, after the prophet whose words are about to unfold.”

The youth kneeled in prayer, the river coming almost to his shoulders, and in this posture raised his head in supplication.

The Baptist’s eyes gleamed. “He is well pleased in you, Isaiah, rise and know that you are purged of sin and in your new virtue are ready to know the Lord.”

The youth stepped forward in gratitude to embrace his benefactor. But the Baptist quickly stepped back, and the nearby Essenes cried out in horror.

>

“He would rob him of his power. He must not be touched when he communicates with God.”

As I wondered how this could be, the Baptist waded back to shore. His sharp blue eyes roved over the multitude, seeming to see everything and everyone in those few moments. He had captured the throng but for a few sneers and crooked smiles. There were always the cynical. I had seen Pharisees and Sadducees in the crowd, and even some publicans, tax collectors, recognizable by their badges of office and the wide berth given them by the people. All feared these toadies of Rome who squeezed from the workers whatever the priests had left them.

I was surprised to see a number of rabbis, bearded and black-robed, with skullcaps and, bound to their arms, small leather boxes, phylacteries, which they kept touching while repeating from the scroll it contained:

“Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One.”

There were even some of my own people there from the surrounding Wilderness, bleak, gaunt-looking hunters and woodsmen. I knew well these people of the Wilderness. It was a harsh, forbidding land, but it was my land, for my people had lived in nearby Kerioth for ages. Here Simon, the last of the Maccabees, made his stand in the chalk mountains near Jericho where the gray slopes are cut by a dark gorge rushing headlong into the Jordan. Here eagles swooped overhead and jackals slaked their thirst where the river wound like a serpent across the glittering sands. It was a land where the Temple and its problems seemed a distant nightmare until I took time to sort out the different elements I saw here.

By and large the motley assembly was made up of the Amharetzin, who, with the native astuteness of the common man, had fallen out of traditional observances of the law because of their disdain for the commercialism of the Temple. They were chiefly menials, employed in carrying off the garbage and sewage, or artisans engaged in carpentry’, smithing, or fishing and farming. They worked in the shops and the bazaars, toiling with their hands, for they had no head for learning. Seldom were they in any of the honorable professions such as law, medicine, or teaching.

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine