- Home

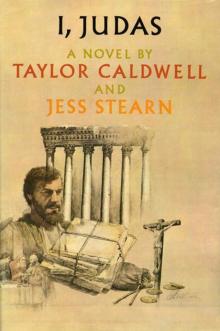

- Taylor Caldwell

I, Judas Page 6

I, Judas Read online

Page 6

They were readily identifiable by their rough dress and manner. I even recognized a few, such as Adam the Tanner, who kept his leather shop on the Street of the Tanners in the Holy City. He was a heavyset man with a grainy face that resembled his own hides. His eyes were small and squinted out on the world with the suspicion so typical of his breed. His companions were as loutish as he, drinking cheap wine from gourds they kept dangling at their sides and talking crudely in loud voices.

Not for the Sanhedrin, but to satisfy my own curiosity, I wandered among them, thinking they might be easy converts to the revolution, for he with little to lose had more reason to chance what he had.

With my hood over my eyes, Adam did not recognize me, though I had frequently patronized his shop, for his leather articles, such as bucklers and cuirasses, were eminently suitable for the troops we would eventually field. Mopping the wine from his beard with the back of his hand, he watched my approach with narrowed eyes.

“What brings you here, Adam?” I asked, enjoying his start at the mention of his name.

If possible, his eyes became even more mistrustful. He looked about uncertainly, as if seeking assurance from his companions.

“How do you say my name?” He advanced on me menacingly.

“It is a well-known name,” I said, relishing my little game.

His reddish face, the wide nostrils flaring, breathed into mine a revolting smell. I drew back involuntarily, the intermingling odor of sour wine and stale garlic almost causing me to retch.

His beady black eyes gleamed malevolently. “I knew it,” he cried triumphantly, “the mucker’s a spy. Look how he’s got himself all covered up.” He thrust out a ham of an arm to snatch back my hood, but I coolly stepped aside. How coarse these creatures were, but useful, as bar-Abbas had pointed out. For what was needed in any battle was not the wise and the thoughtful, but the unwary who would follow their leader to the death, like sheep if need be, without too much counting the cost or the cause.

“Keep back, fool,” I cried in a voice that rang with greater authority than I intended.

Despite all his bravado, he fell back a pace.

“I know that voice,” he said.

“Just as I know your name and face.”

I lifted my hood for a moment, and his eyes widened.

Immediately, his manner became subservient, even craven, for such was the mettle of these fellows.

“What do you here, sir, and in disguise?” he asked in a humble tone.

“That was my question, begging the disguise of course, for I would know you anywhere”—my eyes lightly took in his companions—“by the noble company you keep.”

The unruly crowd was now pressing us before it, and so before we were separated I quickly suggested a meeting, as I was eager to know more about the temper of the people.

He beamed with pride.

“It will be an honor, sir.”

He leered, with one eye closed. “And how is my merchandise holding up?” His voice dropped to a whisper. “You must be outfitting an army.”

I gave him a severe look. “You were not to utter a word, on penalty of instant retribution.”

His manner quickly became servile again. “Only to you who already know it, so there is no harm in it, is there, sir?”

Before I could say anything more, we were cut off by the surging mob.

The Baptist, with his remarkable charisma, quieted them with an outstretched arm. In the ensuing stillness a tall man with a youthful face stepped forward, encouraged by his neighbors. He had the slurring tone of the Galilean, and I wondered what he was doing so far from home. He carried a quill over his ear, and I thought that he might be a Scribe, but he was a scrivener of a different order.

He inquired in a voice strangely without guile:

“Master, is it enough to be baptized to become pure?”

His query touched off a ripple of laughter, quickly silenced by the Baptist’s frown.

He looked the young man in the eye.

“You, Levi, though a publican, will be found worthy in the eyes of the Lord. But it is your destiny to be cleansed by one greater than L”

Levi’s disappointment was apparent.

“Since you know my name, never having known me, how can there be one greater?”

“In time your mission will become clear.”

The Baptist’s growing fame had drawn pilgrims from all over the land. They were eager for miracles. “Baptize us. Master, baptize and heal. Heal, heal, heal.”

They crowded about him in their zeal, clutching at what little clothing he wore, but were flung back by a determined ring of his own followers.

His eyes searched the crowd. Some, chiefly the Amharetzin, were sparsely clad, barefoot and in rags. Others were in elegant robes, with tunics of silken gold and silver slippers. His piercing glance seemed to probe beyond the fine raiment, and many grew uncomfortable under his gaze. In this mood, his powerful voice burst on them like a clap of thunder. “Who,” he cried, “has warned you to flee from the wrath to come?”

The uneasiness settled over the crowd like a cloud, and I was minded of the chiding of the prophet Jeremiah. Could he indeed be Jeremiah reborn, as some thought, or Elijah, the trumpeter of glad tidings, as others rumored? Whatever, or whoever, he held the crowd prisoner.

“Repent like young Isaiah, and be not pious before the multitude. Bring fruits worthy of repentance, and say not smugly within yourselves, as do the Sadducees and Pharisees, we have Abraham the patriarch to our Father. For I say unto this generation of vipers that God is able of these stones about you to raise up many children unto Abraham. There is nothing sacred about the twelve tribes not sacred before God. The High Priests forbid the Samaritans, the Idumeans, and yea, the Essenes, to worship in the Lord’s Temple in the God-given City. So I say unto you that this Temple is no longer the Temple of the Holy One, but of the vipers who serve the God of Herod and Rome.”

The skies trembled with the applause of the disinherited, the selfsame Amharetzin, while the dark looks of some indicated they might be Pharisees or Sadducees. It was small wonder the High Priests wanted a report on the Baptist. He was never more devastating than in attacking their stewardship. “As we all know,” he declaimed, “two families dispute the miter of the priesthood, those of Annas and Boetus, who has long been out of power because of the fecundity of Annas’ loins. But the dried-up Annas has run out of sons, and now has only sons-in-law to collect tribute from Jews scattered around the world. For if they tithe not, the Lord God of Israel will not welcome them to worship.”

The Essenes and the Amharetzin laughed uproariously, for his voice was heavy with sarcasm. “The Talmudic scholars have a saying: ‘Woe is me for the house of Boetus because of its measures. Woe is me for the house of Annas and the hissing of the vipers. They are the High Priests, their sons are the treasurers, their sons-in-law the officers of the Temple, and their servants belabor the people with staves.’”

As he went on in this vein, I quietly took stock of him. He was tall, taller than me, and his gauntness added to the impression of height. His arms were thin yet corded with muscles, and with the fanatical gleam of his fiery eyes he seemed to exude boundless energy. A camel-hair tunic fell to his hips, and he was spared nakedness by the flimsiest of loincloths. From what I had heard, his wants were simple. He ate but a few figs and dates a day, a little bread, honey and locusts, and once a week a morsel of lamb or fish. He was an Essene, and so a celibate. But in his intense single-mindedness, I am sure he never gave it a second thought. His was a world of ideas. His Essenes, like himself, came from the monastic center of Qamram on the Dead Sea. They were of a grim and forbidding nature. Fierce and wild-looking as their Master, they vehemently registered their approbation whenever he attacked a familiar target. They held themselves scholars and devoted their lives to interpreting the law. Except for their devotion to the Baptist, they appeared to have withdrawn from the mainstream of life. They seemed to regard everybody wit

h suspicion. I was glad of the hooded cloak which veiled my eyes, for it hid my contempt for their senseless rigidity. They owned no property, employed no servants, not even at harvest. They would neither eat nor drink on the Sabbath, nor even empty their bowels on this day of rest. They would not take an oath because they believed in speaking only the absolute truth and thus saw no reason for reaffirmation. They offered no animal sacrifices, saying it was enough to keep the covenant of Abraham, and so were excluded from the Temple in Jerusalem. Annas and Caiaphas had no use for Jews who did not swell their coffers, just as the Baptist had no stomach for the Temple hypocrites. Since his father was a Temple priest, it seemed odd that he should take so opposing a course. However, he was little different in this respect from me, for none was higher in the Temple councils than my father. Yet, even with my passionate desire for freedom, I could never become a monk like the Baptist.

They said that the Baptist had superhuman powers. He could walk endlessly through the hot desert and over the frosty mountaintops, going without food for days and not requiring water like other men. He could talk for hours without tiring, and it was his practice, from time to time, to single someone out of the crowd, nearly always the physically afflicted. It was no wonder that some thought him the Messiah, for he truly seemed sent of God. With all his fire and passion and the spell in which he held his audience, I could easily see in him another Judah Maccabee, ready to spring out against the tyrant. He was the embodiment of everything I hoped for. And he fitted the prophecy, even to being born a Judean close to the time predicted for the birth of the King of Kings.

He moved his arms eloquently as he spoke, and I could visualize that strident voice and those compelling arms summoning Israel to battle. His power was manifested in his remarkable healing abilities. It didn’t matter who the person or what ailed him. He would merely touch him, piercing him with a hypnotic stare, and the healing would be accomplished. Sometimes there was a mental problem, and he would drive out the devil from the demented one.

“Why do you wonder so?” he asked the marveling throng. “You believe in Elijah, who healed whoever came to him, so why question whoever is sent by the same?”

His healings gave him credibility; otherwise he might have seemed just another street-corner orator. Still, I sensed in him a presence so ethereal that it seemed not of this world but a tenuous link to the God he invoked with such passion.

He seemed to work himself up by degrees, artfully connecting the Temple to the Roman authority.

“Worse than the Romans,” he cried, “are the Romanizers, and none is worse than Herod Antipas, a true son of the godless Herod, called the Great. The Great One raised monuments to his Roman friends. He built the Fortress Antonia, from which Rome watches over the Temple, and brazenly dedicated it to the triumvir Mark Anthony, despised even by the Romans as a dissolute rake. This evil king constructed forums, theaters, circuses, public baths, all in the Hellenic-Roman manner, and prided himself on being more Greek than Jew. Even while building a Temple for God in Jerusalem, he set up statues of Augustus for Jewish worship. He looted the graves of David and Solomon and created the great Mediterranean city of Caesarea for the conquerors. And there the plotting Pilate sits today when not in the Antonia overseeing the massacre of pilgrims.”

There was a sharp intake of breath among the throng. Some faces grew hard with anger and some eyes grew moist. For all Israel understood that this senseless slaying was a thrust against them. The Baptist’s voice rose emotionally. “These were Galileans who died, but what protest did the son of Herod make? Herod Antipas was busy with other matters, reveling in his palace in Perea with the adultress he calls wife. What was the law of Moses to this wicked man who stole his brother’s wife? Like the Romans, he lives for the flesh, but he is worse than the Romans. They are pagans and know no better, while he fancies himself a ruler of the Jews and mouths the law. And still we pay tribute to both.”

The Baptist raised his eyes to the skies, and I saw them take on a radiant light. “Beware, you sinners, for one comes who will purge the wicked of their Godlessness. He is closer than any dream.”

I could tell from their faces that the crowd was stunned.

This oblique reference to another was unexpected and disconcerting. Did we have to look still further when our search had seemed finally over? My only fear had been that his polemics against taxes would bring Pilate and Herod and their minions down on his head. And now we were confronted with fresh uncertainties. Was he only another Jeremiah, scolding, when the time had come for action? But he did have the faculty of moving his listeners. He spoke not directly of revolution, yet he planted the dissension which is the partner to insurrection. He was not as simple as he seemed. But like a true prophet, he spoke sometimes in roundabout terms meaningful only to those familiar with the law. What Roman, what heathen, could understand as he shouted out: “And now also the axe is laid unto the root of the trees. Therefore every tree which fails to bring forth good fruit is hewn down, and cast into the fire.”

Levi the Publican was as astounded as I was. He raised a hand to inquire: “Then the law of Moses, which gives preference to the twelve tribes of Israel, is subject to alteration by mere man?”

The Baptist shook his head slowly. “I baptize all who repent with water, but that soon will no longer suffice. For he who comes after me is mightier than I. He shall baptize with the Holy Ghost, and with fire.”

It seemed incredible. For if there was one mightier than the Baptist, he was a mighty prophet indeed.

“It is no virtue alone to be baptized,” he continued, “wherever there is water and someone thinking to be made holy. But without a true wish for salvation the immersion is useless. And so we baptize only those of an age truly to repent.

“For as the prophet Ezekiel said: ‘I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you shall be cleansed from all your filthiness, and from all your idols will I cleanse you as well.’ But that is not enough. There is no salvation in being cleansed, not even of Ezekiel, but in being reborn. And that comes not through me, but through the one of whom I speak.”

I could sense the crowd’s restlessness whenever he mentioned another than himself. Some had come a long way, braving the deserts and the mountains, for a glimpse of the new Elijah. Surely they did not want to hear that they had made the journey in vain.

The Essenes, of course, closed their ears to his self-deprecation.

“Master, Master,” they cried, “no man of woman born is greater than you.”

He smiled, and I realized then, seeing his face shine like the sun, that his features were usually set in a scowl.

He had spoken for hours, neither eating, drinking, nor stopping for the ordinary ablutions. He held perfect communication with the assembly, remarkably responding to even unspoken questions. “I will heal no more today,” said he, reflecting my own wonder as to when he would repeat the miracle. “But there will be many healed by their own faith as well.”

His healing had convinced even a number of soldiers in the gathering of his special power. They had been alternately yawning and frowning until young Isaiah’s arm was made as new. They questioned the boy and rubbed their hands over his arm. If the healthy arm were not enough, the boy’s own enthusiasm should have sufficed. There was no doubting his radiance. He was truly reborn.

I had observed the soldiers with some uneasiness. They were obviously not of Rome, for they wore a leather headdress instead of the metal helmet known from the Judean Wilderness to the Northern Islands. Moreover, they had not the Roman’s galling cockiness which made the Judeans less than nothing in their own land.

But these troops, by the look of them sent by Herod, now seemed as fascinated as the rest by the Baptist. One soldier, most likely a Samaritan mercenary, seemed pleased by the rebuke to the tribal aristocracy. “What then shall we soldiers do, who must do the bidding of our masters?”

“I care not what your masters say. Do violence to no man, neither accuse any falsely, and be con

tent with your wages.”

On one hand he advocated sedition, on the other he advised them to be good soldiers. Herod would indeed be baffled by this enigma.

Encouraged by his response to the soldiers, a well-dressed man, a rich merchant, judging from his purple cloak, raised his hand.

“I am of the illustrious House of Benjamin …”

“The Baptist cut him short. “Again I say to the seed of Abraham, there is no promise of a continuing covenant without salvation, and salvation comes not arbitrarily to the people of the promise.”

“Is there no salvation for this son of Abraham because he is of Abraham?”

“Not because he is of Abraham any more than because he is not of Abraham.”

“Then what brings salvation for such as I?” The words were humble, but not so the demeanor.

The Baptist’s voice held a cutting edge. “If you would truly repent, take off your fine cloak and give it your neighbor who has none,”

“Then,” smiled the merchant, “he would have a cloak and I would have none.”

“The Lord,” said the Baptist, “notes what is given and what is received.”

“Is it better to give?”

“Who asks unless he has never given?”

The blood came to the already florid face. The merchant quickly slipped off his cloak and held it disdainfully in the air. No groping hands reached for it, and with a shrug he finally put it back over his shoulders.

A bemused look came to the Baptist’s eyes. “They know you, merchant, better than you know yourself.”

The man seemed to shrink within himself, and slunk away, the Baptist’s words following after him:

“If you have meat and your neighbor has none, impart that also to him.”

Testimony of Two Men

Testimony of Two Men Wicked Angel

Wicked Angel The Arm and the Darkness

The Arm and the Darkness Answer as a Man

Answer as a Man Grandmother and the Priests

Grandmother and the Priests On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir

On Growing Up Tough: An Irreverent Memoir Ceremony of the Innocent

Ceremony of the Innocent The Listener

The Listener Bright Flows the River

Bright Flows the River The Earth Is the Lord's

The Earth Is the Lord's Dialogues With the Devil

Dialogues With the Devil A Tender Victory

A Tender Victory This Side of Innocence

This Side of Innocence To Look and Pass

To Look and Pass The Strong City

The Strong City Balance Wheel

Balance Wheel A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome

A Pillar of Iron: A Novel of Ancient Rome Glory and the Lightning

Glory and the Lightning Dear and Glorious Physician

Dear and Glorious Physician The Wide House

The Wide House The Final Hour

The Final Hour Never Victorious, Never Defeated

Never Victorious, Never Defeated Unto All Men

Unto All Men The Turnbulls

The Turnbulls Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith

Your Sins and Mine: The Terrifying Fable of a World Without Faith The Eagles Gather

The Eagles Gather Let Love Come Last

Let Love Come Last The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny

The Devil's Advocate: The Epic Novel of One Man's Fight to Save America From Tyranny A Prologue to Love

A Prologue to Love Maggie: Her Marriage

Maggie: Her Marriage The Late Clara Beame

The Late Clara Beame Melissa

Melissa Great Lion of God

Great Lion of God Captains and the Kings

Captains and the Kings Dynasty of Death

Dynasty of Death No One Hears but Him

No One Hears but Him The Sound of Thunder

The Sound of Thunder There Was a Time

There Was a Time Time No Longer

Time No Longer I, Judas

I, Judas The Devil's Advocate

The Devil's Advocate The Romance of Atlantis

The Romance of Atlantis A Pillar of Iron

A Pillar of Iron On Growing Up Tough

On Growing Up Tough Your Sins and Mine

Your Sins and Mine